Listen to this episode and find out more about it at theallusionist.org/cairns

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, try to find the puncture repair kit because language sprang a leak.

Today’s episode is another with someone I met at this year’s Dictionary Society of North America conference - or DicCon, as a friend insisted on calling it.

This episode concentrates on some English language dictionary history, but I’m very keen to know about lexicography in other languages and other cultures if you have any appetite to tell me about it.

On with the show.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: It is kind of wild to think that we could take one component of the language, that is words and their meanings, which, language is more than that. Language is both the lexicon and the grammar, how we string those words together, and then also how we convey those words vocally, written, in sign, so on and so forth. So it's wild that we would take just the words and talk about what they mean in a way that was universal and shared. Because that's not actually how the language works. And in fact, this was a very odd idea when people first started doing it. John Florio made a dictionary of English and Italian, where he said, "I know y'all are gonna think I'm nuts for trying to do this, but I'm gonna tell you just the words, even though, words are women and, and sentences and full grammar is a man.”

HZ: Yes. Those are the genders.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: So the idea that we could just have a dictionary that's only words is already a little bit wild in terms of how language works. I'm coming off as a total dictionary hater, but...

HZ: No, I don't think so. You wouldn't have dedicated your life to these topics if you disliked them, right?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Yeah. There's nothing to make you hate a dictionary like studying it, though...

HZ: I think that's with everything, isn't it?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Yeah, I know; you always regret what you choose to study.

My name is Lindsay Rose Russell and I study dictionaries and the history of dictionary making, with a particular interest in weird dictionaries. I also teach at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

HZ: And Lindsay Rose Russell is the author of the book Women and Dictionary-Making: Gender, Genre, and English Language Lexicography.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: I wrote a book about women and dictionary making, with the scintillating title Women and Dictionary Making, partly because I had, in the course of studying the history of the English language, come across some things that felt contradictory to me. I had seen that a number of early modern dictionaries were addressed to women in their title. So Robert Cawdry's 1604 Table Alphabeticall, which is largely understood as the first monolingual English language dictionary, includes in its title that it's for ladies, gentlewomen, and any other unskillful persons.

HZ: Ooh! 'Unskillful'.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: And that is normally sort of a punchline in a lot of dictionary histories and dictionary conferences. It's one of our best jokes. But that didn't sit so comfortably for me with some other things that I had learned about the place of dictionaries: that women were not always unskillful, obviously. For instance, the first monolingual dictionaries, many of them were addressed to women as readers and audience members.

HZ: The second known monolingual English dictionary, John Bullokar’s An English Expositor: teaching the interpretation of the hardest words used in our language, with sundry explications, descriptions and discourses, was published in 1616 and addressed to ‘greatest Ladies and studious Gentlewomen’. Thomas Blount’s Glossographia, a hard words dictionary published in 1656 - and the first English dictionary to include etymologies - was “chiefly intended for the more-knowing Women, and less-knowing Men.” Women at the time were not allowed to access much of the education available to men, so dictionaries were offering to fill some of the gaps. While a lot of the dictionaries were addressed to women as a category of people, many were also dedicated to specific women, because they had funded the dictionaries. So women were the intended audience for the dictionaries; they were the patrons of the dictionaries; and then they were also doing a lot of work compiling the dictionaries, often unpaid and uncredited.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: The Oxford English Dictionary had been a place where many women had volunteered as readers, contributing quotations that informed different senses of dictionary definitions. Those are real lexicographical labours, and they tend to be discounted as just charming, amateurish hobbies of overeducated women. And that made me wonder what the more complete story might be about dictionary making. There are a great many women who were involved in dictionary making, not just recently or in the closer past, but dating back to 1486, there are women making dictionaries of English terminology. So, I was both pleased and enraged to discover such a history existed.

HZ: Yeah, what a mixed blessing be like, “Oh cool, they did exist, but no one really talks about them,” and there's all this work that has just been hidden under the Big Daddy Dictionary image, where it's like one single minded man doing brilliant stuff. Is that a true thing that happened? A single minded man doing brilliant on his own?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Definitely not in the case of dictionaries! Merriam-Webster, the flagship definitive dictionary of the United States in some ways, claiming its lineage from Noah Webster, a single man working alone - that one actually might be true, because everybody disliked Webster in his time and after.

HZ: How did Merriam get sucked into that mess then?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: That was after Webster was dead.

HZ: He’s just much easier to get along with now he's dead.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: One of the histories of lexicography is called The Dictionary Men: Their Lives and Times. And The Dictionary Men, Their Lives and Times covers what I refer to as the lexicographical trinity that is Johnson, Murray, and Webster. And those men are largely styled as working alone, even though Murray's granddaughter Elizabeth Murray wrote Caught in the Web of Words, which is an amazing biography of him, that's mostly a biography of the dictionary itself and dictionary making, which is an amazing thing. And in that book, she's very clear that there were a ton of other people working on the dictionary over the course of that time. She reveals a really beautiful portrait that was not only about the global contributions of men and women to the OED, in a variety of roles, she also has a chapter in that that's called 'The Dic and the Little Dics'. And it's about Murray and his children and the sort of spectacle that they created in Oxford as a family. And famously all of those children did chores working on the Oxford English Dictionary. As soon as they could read, they had to read and sort slips that had been sent in from readers that were citations that could go into the dictionary. And then the daughters also gave tours of what was called the Scriptorium, where they made the dictionary, which was a shed in their backyard. They were responsible for the spring cleaning of the shed, and giving tours to visitors. And Murray's wife, Ada Murray, was like a business partner. She helped him with all of his professional decisions; she also did research on the dictionary; it was her idea to build the shed in the backyard for the dictionary to be made. She also served as an amanuensis and correspondent for him, so she would answer some letters on his behalf.

HZ: 'Amanuensis' is one of those words I always have to look up. The 'manu' is from the latin for hand because it's referring to people who copy text or write dictation. I'm hoping the etymology will help me remember what ‘amanuensis’ means henceforth.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: It was really a very much a family affair, and I think that the collaborative nature of the Oxford English Dictionary is acknowledged, but in the telling of that story, the place of women tends to be as this sort of sweet, nice, family supportive story that, "Oh, isn't it cute that Ada helped him with the scriptorium?"

HZ: A lot of the great men of dictionaries were working at home, so their wives were effectively office managers, and domestic labour was also dictionary labour. But there was more to it than that.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: These are necessities of lexicography. Many, many large scale dictionaries relied on precisely this kind of incidental labour, which is to say that men living in homes with women relied on those women to do tasks that were directly related to both the mundane work of dictionary making - cleaning the scriptorium, sorting slips - but also the more intellectual efforts of dictionary making, that are doing ad hoc research on a word, going to the Bodleian to research some etymology, or in the case of another of Murray's daughters, writing an introduction that counted up all the words from all the different languages, and how many entries there were, and subentries, and things like that, so, writing a preface to the dictionary.

HZ: These women were doing editorially essential work. Jessie Craigie, the wife of OED editor William Craigie, had to sort through all the words that began with ‘un-’. Or, to pick a modern example: Green’s Dictionary of Slang, which was published in 2010, is an almighty achievement where Jonathon Green spent seventeen years compiling 100,000 entries of more than 500 years of English slang. And Jonathon Green’s wife, Susan Ford, went to the library five or six times a week for a decade to search for citations for his dictionary.

HZ: Why do you think that was an abiding image then, and why do you think it's still attractive now, that it's like one lone genius man working on his own in a shed that he had the idea to build?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: …I don't know.

HZ: Is it coming from the men, or is it coming from the outside? Is it hard to tell because that has been so much of our recorded culture?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Right. In the case of Murray, I don't think James Murray felt like he was alone in making the Oxford English Dictionary. I think he was keenly aware of himself as a part of a very large and many tentacled team. In a lecture he gave in 1900, he talked about every lexicographer as adding their stone to the cairn. You know, cairns like the little things when you go hiking that are piles of stones that tell you you're still on the right path. So I think Murray understood his own work as contributing to a larger lexicographical project where he was not a lone dictionary maker in the effort of dictionary making more grandly. But, I don't know; in history, I think it's easier to tell the story of a singular man. Because of course it's easier to tell the story of a singular man, as opposed to the story of thousands of people working on a single dictionary and doing all different kinds of things.

HZ: Female lexicographers weren't just putting stones in men's cairns though. They built their own cairns.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Women are credited as compilers of dictionaries throughout the history of the English language, and they make dictionaries of all different kinds, multilingual, monolingual, specialized - so dictionaries of religion or math or botany - a lot of domestic handbooks that also include medical handbooks, so sort of spreading what we might think of as conventional male female divides. So there have been a lot of very weird, small, strange dictionaries from the very beginning of time of dictionaries. I love weird dictionaries. I love small dictionaries. I love ones that are handwritten and then photocopied and circulated, or sold on colorful tables, in the bookstore they’re next to the little rubber ducky pen or whatever. I've just always been interested in these smaller projects, because they index the ways that dictionary making is fundamentally a part of everyday life as opposed to the life's work of a single man. One of my favorite dictionaries is a dictionary from 1690 called The Fop Dictionary by Mary Evelyn.

HZ: The Fop Dictionary, full title Mundus Muliebris: or, The Ladies Dressing Room Unlock'd and Her Toilette Spread In Burlesque. Together with the Fop-Dictionary, Compiled for the Use of the Fair Sex. It contains a recipe for a water for your face which distills a roast pig or 9-day-old puppy with butter, booze and two peeled lemons. There is a long poem about ladies all dressed up. And there's a glossary of fashion- and grooming-related terms - many of which are to do with hairstyles, such as ‘Favorites’ which are "Locks dangling on the Temples" - not to be confused with ‘Cruches’, which are "Certain smaller Curles, placed on the Forehead." Mary Evelyn likely was having some fun with this - she was young when she wrote The Fop Dictionary, she died aged only twenty, and her father John Evelyn got the book published five years after her death.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: For Mary Evelyn, it's clear that she enjoys these terms of fashion. Mary Evelyn's dictionary is describing this ephemeral, fashionable language that she doesn't imagine is the definitive reference for all time. She's not trying to necessarily teach people a language. She's trying to celebrate and encourage female speakers to embrace this language. So she is not involved in a lot of the other linguistic anxieties that other speakers, and specifically male speakers, might have had around the same time. The dictionary itself champions the borrowing of French terms, which are the language of fashion at the time. So there's a lot of what was then a promiscuous lexical borrowing that she was advocating, which is a famous feature of women and English language, is that they have often been innovators, the first to adopt new words, new grammatical structures, things like that.

HZ: Something I learned from alumsionist Gretchen McCulloch's book Because Internet is that if you want to see where language is going, pay attention to how teenage girls and young women are using it, because they're usually 10-15 years ahead of the curve. Not just a modern pattern, if it's happening in the late 1600s with The Fop Dictionary. So women were involved in lexicography, and making their own dictionaries themselves.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: The thing that's notable, though, is that women rarely are credited as primary editors of general purpose, monolingual English dictionaries, the kinds of things that we tend to think of today when we say, like, "That's not in the dictionary," to tell someone that they've said something that we don't like normally, that that's not a real word. Women were not welcome in that publishing domain, not until at least the 20th century, and even then, not until quite late, in like the 1980s, do you see staffs and editors of dictionaries who are women. Large scale lexicography requires a lot of work and leadership, and that has rarely been entrusted to women, who are perfectly capable of doing it, and do it in some degrees in the shadows.

One thing that I think will happen in the coming years is that we are likely to see more periodic outrage more frequently, given that lexicography as a field is shrinking.The number of working lexicographers at any mainstream publishing house is diminishing, which means that there are fewer and fewer updates to different definitions. Dictionaries are getting smarter at targeting where their definitions might be weak or problematic in some way and anticipating that, doing full scale revisions of terms to do with gender and sexuality, with race. But with fewer people to do that work, dictionaries are still often relying on old definitions. And, to complicate that, technology companies are licensing from outdated dictionaries.

HZ: Why? Because it’s cheaper to license a really old dictionary than it is a current one!

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Therefore, when we're looking at Google or Kindle or other places on our phones and our computers, we are often seeing definitions from old dictionaries. And those old dictionaries are bringing with them old ideologies, about who counts as human and who's legible in what ways. So we're more and more vulnerable to dictionary making that is not in keeping with egalitarian principles of life and living.

HZ: Part of the problem is that to appear in the dictionary, a word must have proven use in writing. And although nowadays dictionaries can put whatever they want into their online editions, and do an outrage-inducing press release about how they have added a word that arose from a TikTok trend, the vast majority of dictionary definitions are based upon citations of written words published pre-21st century. And who was most likely to get to publish written words pre-21st century?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: We know that there are biases in print, and we know that there are biases in publication: who gets to publish, who gets to see their work edited and printed, is a rarefied class of writer. So those typically are written by white, straight, dead men.

HZ: I remember a few years ago, there was a scandal about sexism in sample sentences. I think it was 2016. They had ‘rabid’ being demonstrated by ‘rabid feminists’.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: In instances like 'rabid feminist', it's not surprising that ‘rabid feminist’ would be amply evidenced in a corpus written by people who think feminists are rabid.

HZ: But that's not a new kind of scandal at all, is it?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Absolutely not. And that scandal happens almost like clockwork. As a researcher of this, it's infuriating to see it happen every once in a while. It happens with gender, it happens with race, it happens with sexuality, that periodically people will notice that a single definition, or perhaps a handful of them, works on outmoded principles of and ideologies about language or about race or about sexuality or about religion or disability or any number of other things.

And then there will be a protest - and dictionaries to their credit are often responsive. But their responses tend to be confined to editing that single entry or that handful of entries, removing the offending illustration or example sentence. But that doesn't fix anything, is my argument. I think it takes a bigger and more concerted effort on behalf of dictionaries to rethink. So to me, this is all rooted in the fundamental and inescapable fact that dictionaries are white masculinist colonialist nationalist projects at their heart. And an active question I think we should be asking is, do they have to be that? Can a dictionary be something other than that?

HZ: Some dictionaries do aim to be something other than that. For example feminist dictionaries in the latter half of the 20th century.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: There are feminist dictionaries that critique a lot of the principles on which masculinist traditions of lexicography rely. The idea, for instance, that written language is more important than spoken language. The idea that dictionary readers are ignorant, and therefore need to be taught what a word means, as opposed to being interested in dictionaries for other reasons: to be entertained, for instance; to be validated in their own language choices. These are other options for what a dictionary might do, to create community or bring people together. There were a great many dictionaries compiled by women that sort of do feminist work of centering oral language, centering community practice as the basis of dictionary making. They're not only interested in words that have to do with women or that name women. They are not necessarily to do with only the sphere that has been understood as feminine.

The feminist dictionaries emerge in the 1980s and 1990s. And they were published on the heels of quite a bit of very explicit critique of dictionaries in the 1970s. And the thing that's interesting to me about them is that the critiques of dictionaries that came out in the 70s were often women looking up words in dictionaries and being like, "Wow, that's rude. You have just described women as ignorant or incapable. One solution to that would be to fix those problems in specific words and definitions.” So that's something that I think feminist dictionaries have been good at doing, is acknowledging who uses a word, when.

HZ: For instance, they might make it clear that a word is a slur when some people use it; but used within an in-group, that same word might be a term of endearment. These dictionaries make it clear that the word is not the same for all its users.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: And I think that a lot of those things are really, really important to what a word means, when and how. But also admissions that, you know, funding is scarce and the ability to publish a new edition of this dictionary is maybe not so likely. Whereas the Merriam-Webster mainstream dictionary types will presume in the next edition there will be corrections, feminist dictionaries assume that might not be a reality and instead leave that kind of correction and annotation to readers themselves - so they often have blank pages and encourage readers to include their own senses and entries in their dictionaries.

And their prefaces are delightful and wacky. There's a lot of dedications to cats -

HZ: They did a lot of reading.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: - admissions that cats and moonlight were really important to their work process.

HZ: That’s nice.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: And feminist dictionaries are explicitly feminist. Many of them include feminism in their title or described in their own prefaces their political and theoretical leanings toward feminism.

HZ: Was it a problem for these dictionaries to have the word ‘feminist’ in their title?

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: Probably, because a lot of them get renamed over time to more and more ridiculous things. Historical Dictionary of Feminism, also known as Goddess to the Glass Ceiling. One that is renamed, or that also went under multiple names at the time, is The Feminist Dictionary from 1973. That one largely focuses on some words that are used to disparage women or definitions that ultimately cast women as terrible. That's almost like a trigger warning dictionary that helps women be prepared for the kinds of sexism they will encounter in a mainstream dictionary.

HZ: It got retitled to: An Intelligent Woman's Guide to Dirty Words.

LINDSAY ROSE RUSSELL: One of them starts out as - A Feminist Dictionary is the title. So A Feminist Dictionary becomes Amazons, Bluestockings and Crones, which obscures the fact that it's a dictionary at all. And that's a popular reception of these dictionaries, that they're not actually dictionaries, that they're really sort of comical pieces, or that they're supplements to dictionaries - almost like genre play, like The Office just pretending to be a documentary, they were just pretending to be dictionaries, they were not real dictionaries. But I think that everything internal to these dictionaries suggests that they are dictionaries earnestly and in their own right. The retitling of many of these dictionaries tends to take the punch out of the initial project that is one that both critiques lexicography as it exists in mainstream forms and tries to reimagine in a really fundamental way what dictionary making could be and what dictionary use could be. So a definition doesn't just settle something, answer the question that you've come to the dictionary to have answered, because they don't think that their audience is an ignorant human who's in need of some light teaching by a book. Instead they present, often, definitions as ongoing debates and negotiations of meaning, and also meaning in contextual space.

Feminist dictionaries are not interested in adding more words that might be more common in feminized speech, nor are they interested in sort of patching up the places where women are presented as passive or ignorant to the active and all-knowing man. They're actually trying to reinvent from the ground up dictionary making. They come from a different philosophy of language even, and then try to bring that philosophy of language into the dictionary.

HZ: Lindsay Rose Russell is an academic who studies dictionaries and dictionary-making, and her book is Women and Dictionary-Making: Gender, Genre, and English Language Lexicography.

Next episode: one of your favourite lexicographers returns to the show.

The Allusionist is now available to listen to on BBC Sounds in the UK! Which you know if you’re listening to this bit on BBC Sounds. There are some other dictionary episodes in the back catalogue: as well as the last episode on Project ENABLE, there’s The Authority, where Kory Stamper talks about being a lexicographer for Merriam-Webster; and we heard all about how Dictionary.com’s Word of the Day is chosen in the episode called Word of the Day. Go all the way back to the early days of the show and you can hear about mountweazels, the copyright trap words put in dictionaries to catch people who copied the text into their own dictionaries! Although Dictionary.com just announced it has added ‘mountweazel’ to the dictionary proper, so I guess if ‘mountweazel’ is now enshrined in the dictionary as a decoy word, then it is no longer going to work for its original purpose of being a copyright trap word. So in officially recognising ‘mountweazel’, they ended it.

The Allusionist is an independent podcast kept afloat by you: if you want to help out a small independent podcast for free, recommend it to someone; if you have two dollars a month going spare then you can also go to theallusionist.org/donate and not only fund the pod, you also get regular livestreams with me and relaxing readings from my collection of dictionaries, a different one each time; you get bespoke alarms and ringtones voiced by me - yes, I’ll still do one for you even though the deadline for submissions is passed, because if anyone is late to a deadline, it is me - and best of all, you get to hang out in the Allusioverse Discord community chatting about ink and portmanteaus and professional fart maids. Join us at theallusionist.org/donate.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

geniculate, geniculated, adjective: bent like a knee; jointed; knotted; verb transitive: geniculate, to form joints in; noun: geniculation. Latin: geniculatus, geniculum, a little knee - genu, the knee.

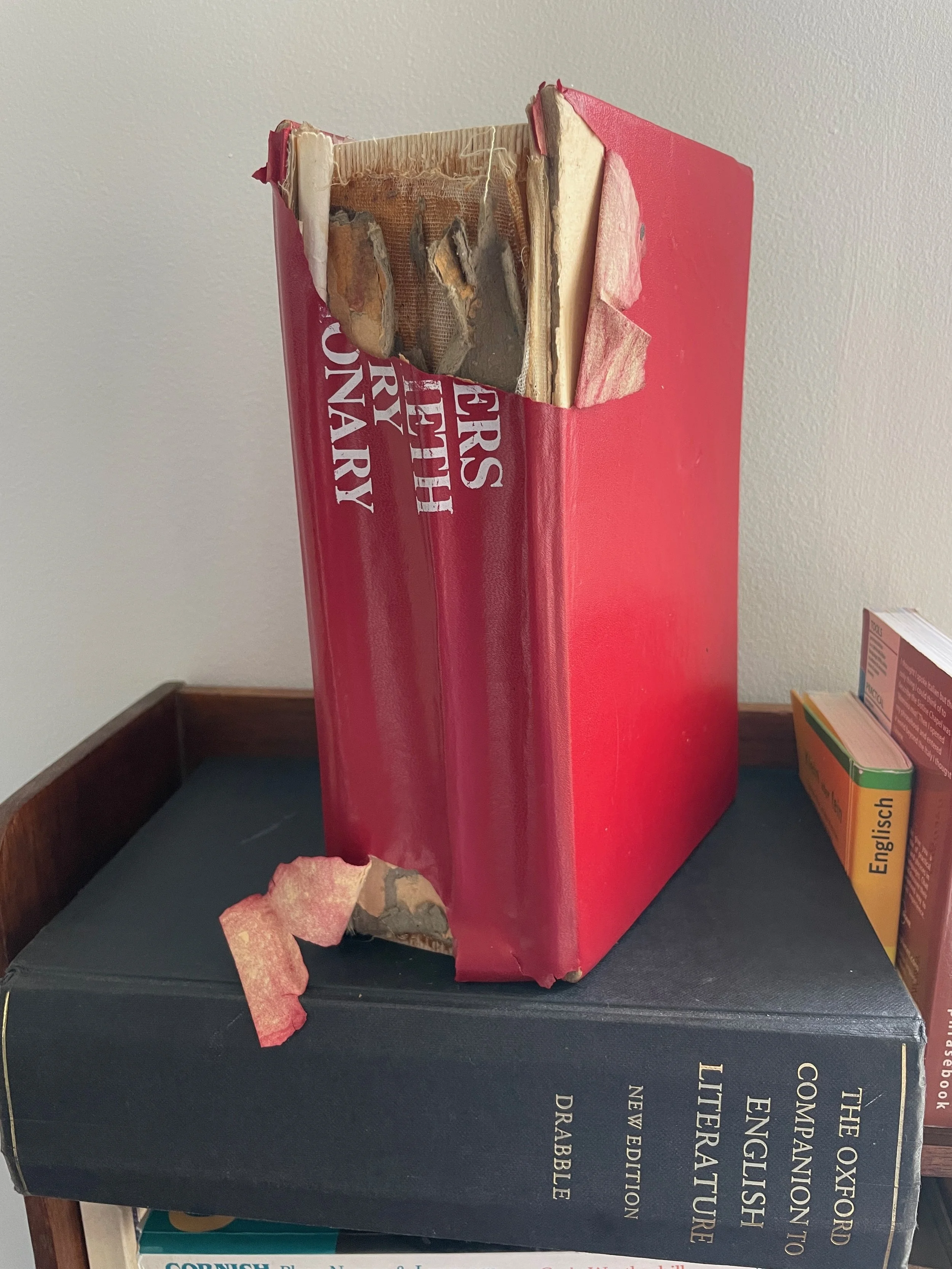

I’m randomly selecting the words from a disintegrating edition of the Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, 1972 edition, which was the dictionary of the Zaltzman household throughout my childhood. And only very recently did I learn about this provenance: my parents were out shopping for anniversary gifts for each other, and they bumped into each other at the bookshop buying each other the Chambers dictionary. Cute story, you might think? Not really, they interpreted it as a sign that they should never buy each other an anniversary gift again, and they made it through 52 years of marriage without celebrating their anniversary.

Anyway, try using ‘geniculate’ in an email today.

This episode was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman, with editorial advice from Martin Austwick, who also composed the music. Hear it with vocals at palebirdmusic.com.

Our ad partner is Multitude. If you have a product or thing about which you’d like me to talk, sponsor the show: contact Multitude at multitude.productions/ads.

Seek out @allusionistshow on YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, BlueSky, and Twitter still. And you can hear or read every episode, find links to more information about the topics and people therein, and see the full dictionary entries for the randomly selected words, all at the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.