Visit theallusionist.org/siblings-of-chaos to listen to this episode and obtain more information about the topics therein

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, shiver language's timbers.

Get ready for nautical etymology, and trees and gas and internal organs and cows. An alumsionist returns to bring the joy.

But first: if you have some spare change, throw it into the virtual bucket at theallusionist.org/donate and in return you get to keep this show going, you get missives with behind the scenes thoughts about every episode, you get fortnightly livestreams with me and my dictionaries - last week we had a very animated discussion about Viennetta, and Frankenstein’s monster’s name - and you get to hang out in the Allusioverse Discord community chatting about etymology and names and knitting and we’ll be watching the new season of Great British Bakeoff together this autumn. Join us! theallusionist.org/donate.

On with the show.

SUSIE DENT: If you take 'tree' and 'true', those two words, back far enough, they're related because if you're true, you're steadfast like a tree, you're mighty like a tree, or loyal, all of that. I love that. There's also sussurus, which is the beautiful word about the rustling of leaves in a summer breeze. Yeah, trees are a big deal. In Japan, they've got shinrin-yoku, haven't they, this forest bathing concept, which I think is catching on a bit over here, is the idea of just going and immersing yourself in nature. And in German, they have waldeinsamkeit, which is forest solitude, which is the same idea of standing beneath a canopy of trees. They are amazing things. And when I describe German, which was my first love, I always remember an obscure quote from Goethe, I think it was, he said that, "English is like a country garden, French is like an ornamental park, and German is a deep, dark wood." And I kind of think that's why I love it so much.

I'm Susie Dent and I am - well, for British listeners, I'm the woman in Dictionary Corner and for non British listeners, I am someone who dabbles in dictionaries.

HZ: "Dabbles".

SUSIE DENT: That's what Ebenezer Cobham Brewer called himself, a dabbler. I feel like I'm that.

HZ: Okay, a deep dabbler.

SUSIE DENT: A deep dabbler. Yes. Don't mention deep dives. I hate deep dives.

HZ: I do too. Why do we hate deep dives so much?

SUSIE DENT: Because everyone's taking them.

HZ: Are they really though?

SUSIE DENT: I feel like that water is not as deep they'd like pretend.

HZ: Well, no, they're not.

SUSIE DENT: No, it's very true.

HZ: They're just diving onto a mirror. At this point in your career of dictionary dabbling, do you know the etymologies of all the words ever?

SUSIE DENT: Nope. Absolutely not. Genuinely, there are very few days where something doesn't pop into my head, something really every day, and I think, “I wonder where that comes from?” Sometimes I can guess. Quite often I can't. So I look it up. So no, I absolutely have not exhausted the dictionary.

HZ: Susie Dent has not one but two new books out: one is Interesting Stories about Curious Words: From Stealing Thunder to Red Herrings. It is absolutely jam-packed with etymology facts along themes from weather to games to bottoms to pub signs. And the other book is Roots of Happiness: 100 Words for Joy and Hope, which is a beautifully illustrated book to make you feel forblissed by language.

SUSIE DENT: It was a lovely thing to work on and very happifying indeed. I came across some research which involves something called emotional granularity, and that is essentially having a large, sufficiently large vocabulary to be able to articulate exactly how you're feeling, to pinpoint your emotions. And so I thought, well, if we can focus on the happy vocabulary, then maybe we will actually begin to feel them. It's like people say, if you smile, you will feel happier; if you laugh, even if you're faking it, you will actually feel happier inside because there's a physiological reaction to it. So I thought maybe the brain, by hearing these words and knowing their meanings and experiencing happiness, if only on the page, maybe it will respond in an emotional way and we can feel happier. So that’s kind of how it started, that actually it would be lovely to round up words that are either lovely to think about, lovely to hear because they trip so beautifully from the tongue, or that have lovely stories behind them. And there are a couple of words in there actually for sad moods but which sound lovely, like the mubblefubbles from the 17th century, which is a kind of fit of gloom or despondency. And I just think if we can say, “I've got the mubblefubbles today,” maybe it might just raise a bit of a smile.

HZ: I liked bellycheer and bellytimber a lot as well.

SUSIE DENT: Yeah. Bellycheer is just so gorgeous because it's just so earthly, isn't it? So bellycheer is comfort food, essentially. It's the food that cheers you up, or that warms your stomach. Then bellytimber is the kind that kind of props it up. So it's the more sort of sustainable type of food, but I like to think it involves a fair amount of stodge. But yeah, where did those go? And also, if you were bellyproud, you sort of wore your portliness with pride and you were ‘ventripotent’, powerfully bellied. So that was quite a good one too.

HZ: Maybe the antifat culture wiped these words out.

SUSIE DENT: Oh well, possibly. You never know.

HZ: Came for the bellypride.

SUSIE DENT: Belly pride! When is Belly Pride day? Or week.

HZ: I liked ‘inwit’ and ‘outwit’ as well. I thought those were very handy and very efficient words.

SUSIE DENT: Yeah, I like that because wit was all about knowing. It was in knowledge. So your inwit was your inner knowledge, so your conscience; and your outwit is your kind of external perception of the world. So it's what you take in by looking out. And I always, always want to add in ‘nitwit’. Because I was thinking, nitwit surely means not having any wits and not having any knowledge. But the dictionary to this day says that the 'nit' is probably the horrible insect that takes up refuge in your hair. Which, to me, sounds all wrong. So I'm contesting that etymology and I'm sticking with nitwit as belonging to outwit and inwit.

HZ: Yeah, we don't know that nits aren't super smart.

SUSIE DENT: Well, exactly.

HZ: We don't know what's happening in their brains.

SUSIE DENT: Exactly. Yes, it could mean you've got the wit of the nit or it could mean that you are dull witted because you've yourself have got nits. Either way, I don't think they belong anywhere near a nitwit.

HZ: The word ‘rival’ was one where I thought, "Oh, this is why we love looking into etymology, because sometimes the stories are so vivid, even when they're not made up.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, rival, originally from the Latin rivalis meant someone sharing the same... river. So essentially competing for the same source of water. And we also get ‘derive’ from there, so we get pulling things from the water, given the importance of transporting things by, rivers and canals. We get a lot of words from the river. And from - this is random because they're not really associated, but from breathing as well, like 'inspire', as well as 'perspire' and 'expire', and 'suspire', to breathe out with a sigh.

HZ: All of these spires are from the Latin 'spirare', to breathe, which also gave us the word 'spirit', because breathing is living. ‘Inspire’: to blow into, as in a divine being was blowing, er, inspiration into you. ‘Conspire’: to breath together. ‘Perspire’: to blow through, and later to blow a watery substance through your pores. ‘Expire’: to breathe your last.

SUSIE DENT: There's also just one record in the OED of a word that I often find quite useful and that's ‘latibulate’. It sounds a bit rude actually, but to latibulate is to hide oneself in a corner.

HZ: That's so useful.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, in a latibule. I think so too.

HZ: For our kind of crowd, that's the word they've been looking for a long time. As well

SUSIE DENT: I am a latibulator.

HZ: I thought a hibernacle would be a very useful thing to have. I want

SUSIE DENT: Strictly speaking, a hibernacle or a hibernaculum is where a hibernating animal goes to spend its winter days. That's how we get hibernium and all sorts, so I just think in human terms a hibernacle is where you retreat to in the winter months.

HZ: I think I need an estivacle, because I'm not a summer person.

SUSIE DENT: Oh, yeah. But do you estivate, do you go and retreat somewhere for the summer or do you just kind of rejoice all the way through it?

HZ: No; I like the soft fruits and the long daylight, but otherwise, the blue skies and things make me very depressed.

SUSIE DENT: Do they?

HZ: Yeah, it's weird.

I thought the etymology of 'gas' was a big surprise as well.

SUSIE DENT: Oh, yes. I would, like you, never have guessed that gas, not in the gasoline sense, but in the - what would you call it?

HZ: State of matter.

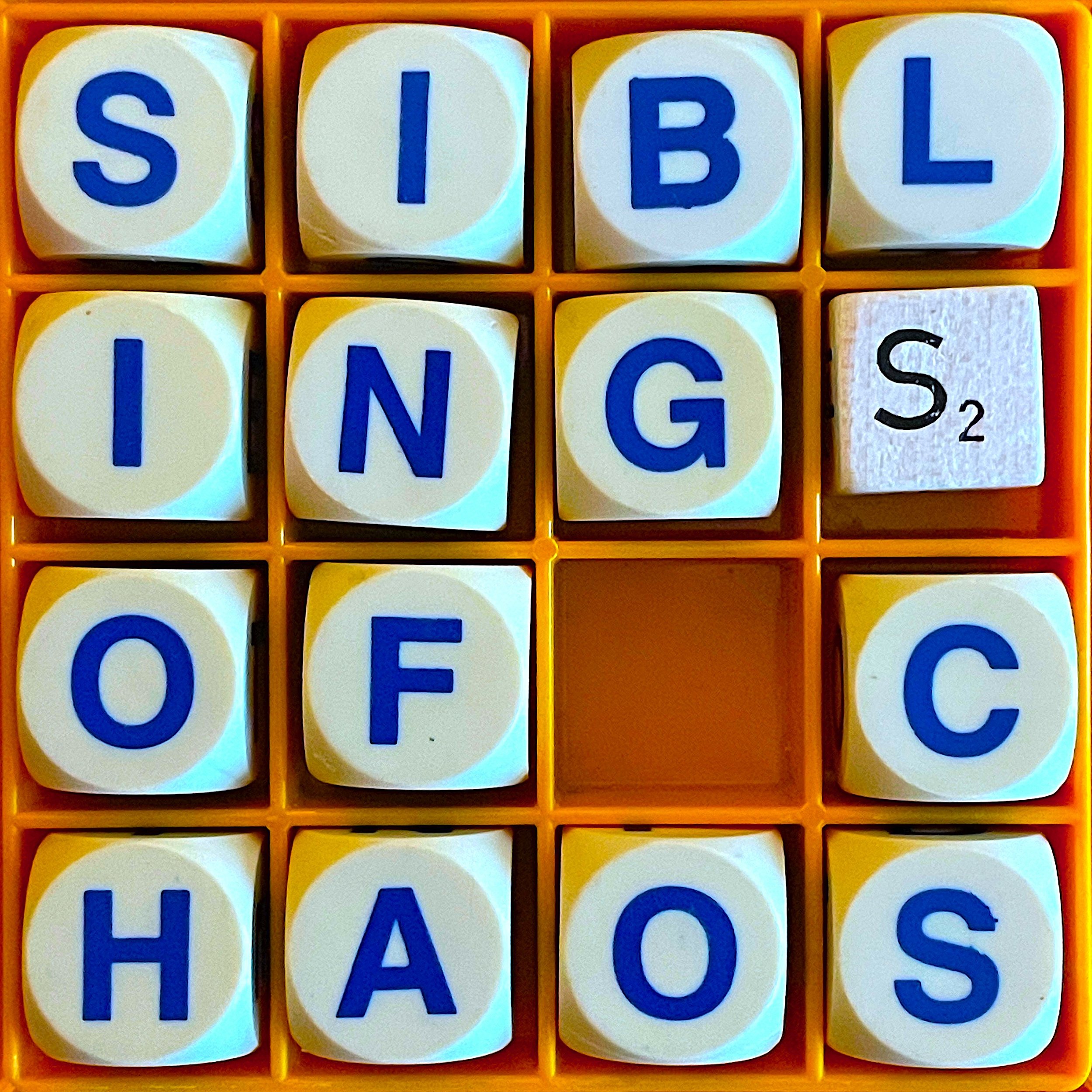

SUSIE DENT: Yes, physical substance, is a sibling of chaos.

HZ: In a sense, we're all siblings of chaos.

SUSIE DENT: I suppose that is very, very true. There was a natural philosopher called J. B. van Helmont, who says, "I have called this vapour ‘gas’, not far removed from the chaos of the ancients." And in turn, he was probably influenced by the 16th century physician and alchemist - I think that's such a good job title - Paracelsus's use of ‘chaos’ to describe the element of spirit.

HZ: Long ago, I talked a bit on the Generation What episode about how the word 'chaos' meant the void before the creation of the world, then by 1600 also came to mean disarray. Around 1615, Jan Baptist van Helmont was conducting experiments whereby he burned 62 pounds of oak, and ended up with only one pound of ash - so what becomes of the other 61 pounds? He deduced they become transformed into what he termed "spiritus silvestre" - a wild spirit. "Hunc spiritum, incognitum hactenus, novo nomine gas voco," he said, "I call this spirit, hitherto unknown, by the new name of gas." And gas was just his more Dutch-inflected way of saying 'chaos'. And if I pronounce chaos more like ‘caas’... ‘cows’, it is a only moderately effortful segue:

HZ: There were lots of cow-related etymologies as well. I suppose it's like, what's important to people? Water supply, breathing, cattle.

SUSIE DENT: Yes. And also just taking the word for cows and cattle from different languages as well. So we've got fellow and a fellow was someone who put down cattle as a sort of trading vehicle, bartered in cattle. That was the first fellow, much as a chap was somebody who sold at a marketplace; it gave us ‘cheap’, and places like Cheapside in London because it had a marketplace in it. And there's also ‘pecuniary’ from the Latin pecu meaning cattle as well, so ‘pecuniary’ meaning relating to finance; that goes back to them as well.

HZ: A lot of vocabulary doesn't even feature the whole animal, just their internal organs. For example the noun 'pluck'.

SUSIE DENT: Pluck: so if you had boldness, if you had tenacity, you were said to have lots of pluck. But originally it was, well, pretty much your heart, I think your liver, your lungs. So the viscera of an animal that were used for food.

HZ: The organs were plucked out of the animal's body as it was prepared to be sold for meat.

SUSIE DENT: Our language is very visceral and a lot of our emotional vocabulary is tied up with our innards, and it was once believed that the heart, for example, is the seat of intelligence, not so much the brain, which is why we learn something by heart, or we record it, and at the heart of record is ‘cordis’, meaning heart. But this is where courage was supposed to reside, particularly again in the heart.

HZ: And the etymology of 'courage' is 'cor', the Latin for 'heart'.

SUSIE DENT: I mean, the heart was really seen as the seat of so much emotion. And our intestines as well: so the bowels were thought to be the seats of compassion, but also courage, and divination was obviously a big thing, particularly the divination of the plucks or the intestines and the bowels. And there's a lovely Scottish word that randomly occurs to me, which is ‘taghaelm’: and taghaelm is specifically foretelling the future by examining the entrails of a sheep beneath a waterfall. How more specific can you get?

HZ: I assume that was something they did enough, then, to require a term so that you weren't examining these sheep entrails anywhere else.

SUSIE DENT: Anywhere else; that had to be below a waterfall.

HZ: I suppose it washes a lot of the gore away.

SUSIE DENT: Ooh, yeah.

HZ: I suppose that's why rivalry - maybe you wanted to be further up the river than where the gut stuff was happening.

SUSIE DENT: Ugh, yeah. Yeah, grim. Grim, grim, grim.

HZ: Seeing how we've somehow travelled from joyful words to grimness, let's consider the word 'dismal', which was from a surprisingly formal diarised misery.

SUSIE DENT: For the Romans, they had the Dies Mali, the Dismal Days or the Evil Days, where it was a really bad idea to do something. I think we should reintroduce these. And, I mean, very, very specific days.

HZ: This pagan Roman superstition of the Dismal Days really caught on in early Christianity and stuck around for about a thousand years - during the middle ages, they had two dismal days scheduled per month! Supposedly these were to mark the ten plagues of Egypt - I know, why are there 24 dismal days per year to mark ten plagues, doesn't add up, well it does if you're a medieval theologian willing to count an additional fourteen plagues that hadn't been plaguey enough to make it into the final draft of the book of Exodus. Twenty-four dismal days in the calendar, the dates varied a bit, depending upon which 900-year-old monastic schedule you're going from, but on those dismay days, they thought it's dangerous to get married, go travelling, start new tasks, do religious rites, get sick, give birth - unless you want your child to have a lifetime of misery, hold it in till tomorrow! Don’t do anything on a dismal day!

SUSIE DENT: Yeah, it's funny, isn't it? I wonder what people did, did they stay indoors? Did they not go to work or were there people who, like the ones who will proudly walk under a ladder in front of other people to show that they really don't care, did they just sort of boldly, brazenly go out saying, “I'm going out even on an evil day.”

HZ: …Just checking my birthday's not on one. But yesterday was one!

SUSIE DENT: Ah. Okay, how was yesterday for you?

HZ: It was okay. Yeah, pretty good. Uneventful.

SUSIE DENT: Uneventful.

HZ: I'll take it.

SUSIE DENT: I'm not sure if the dismal days - they may have involved auspices actually, the people who studied the flights of birds to check which days would be auspicious. And the auspices were also called the augurs, which is why inaugurations took place on a good day, not a bad day. You know, on an auspicious day from the auspex.

HZ: Tell us about the word ‘eucatastrophe’. That was a new one to me.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, Tolkien, J. R. R. Tolkien invented this one to mean an unexpected happy ending. The eu- bit means good, you'll find it in euphemism, so something that is well sounding. So that's a really nice one. I just think, however, that the fact it's got ‘catastrophe’ in it means it's never really going to take over. But he tried.

HZ: Yeah, although catastrophe itself, that just means a turning. So it’s not inherently bad. It's just a reversal in something.

SUSIE DENT: Yeah, that's true. We never apply it to anything good though, do we?

HZ: No, we don't. So maybe they thought, “Even though it's not etymologically particularly loaded, we have to add the eu- prefix to specify it's not one of the negative catastrophes.”

SUSIE DENT: Yes, we've supersized catastrophe, like we do with so many things.

HZ: What went wrong for the word 'vegetable'? Because that came from life and vigour and that's not how people use it now. They use it for a kind of inert state.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, exactly. It's a really odd thing. And it's one of the ones where I suppose it's like semantic bleaching or whatever they call where a word starts out as being quite powerful. And then it just kind of loses its vigour over time and a vegetable definitely has, sadly. It essentially goes back to the idea of being animated in the sense of having the faculty of growth and the most basic attributes of life. But then if we - and I don't think we use this term anymore - if we medically used to describe people as vegetables, which was pretty horrible, it was essentially that they didn't really have any powers of sensation or rational thought. So it's very strange. It's kind of done a real nosedive, that one. But I suppose in the food sense, it's anything that lives as a plant, isn't it, that is growing and has that vigor.

HZ: Yeah. It's an alive state. It's just not a sentient one as far as we know.

SUSIE DENT: No, no.

HZ: 'Silly' did used to mean positive things too, like happy.

SUSIE DENT: Yeah, innocent and nice. Yeah, sælig. How did that happen? Okay, I think it's just basically we looked down on ignorant people. So if you were silly, you were blessed, but also very humble. And so inevitably the kind of peasant associations crept in. And likewise, if you were nice, conversely, you were ignorant - nescius, not having knowledge. It's back to that.

HZ: Well, ‘nice’ flipped as well. But it flipped to the positive.

SUSIE DENT: It flipped to the positive, which is quite unusual. But then, I think it's flipping back to the negative, because if you were to say, "Do you love this hat?” And I would say, “Hmm, it's nice," You would think, “Uh, okay.”

HZ: That might be a very British thing, because there's so much subtext in the words that we use.

SUSIE DENT: Oh, well there is. And also it means 'fine', as in “it's a nice distinction”. They've got such multifaceted personalities, these words.

HZ: 'Fond' was another one that was very mean and then became something affectionate. What are we doing?

SUSIE DENT: I know. So fond was foolish, wasn't it? So, and Shakespeare uses it that way, yeah. Soft in the brain, and then maybe just all a bit gushy and gooey and sweet, yeah.

HZ: ‘Dote’ as well, another one suggesting unsound mind. So I suppose some things do become nicer, but maybe there's always this undercurrent of niceness being undermined by folly. How sad.

SUSIE DENT: Yes. Yes, the dangers of affection. I think there's a lot of morals there that we haven't quite unpacked from etymology.

HZ: Pack them away. Don't open the box. We can't handle it.

HZ: Something I'd like to unpack is why people are always inventing maritime origins for terms. Is it because ships go far away where you can't see them so anything could be happening on there, like them hatching a backronym for the etymologically obscure 'posh'? "Port Out, Starboard Home" - more like Pile Of Smoking Hogwash! I would have gone harder but I didn't want to have to explicit-tag this episode; go forth and coin your own backronym though.

SUSIE DENT: Have you heard of CANOE in etymological circles, the acronym CANOE, which is the Committee to Ascribe a Nautical Origin to Everything? Actually, there are loads that did, to be fair, come from the high seas - but not everything. I think one of my favourites is the slush fund. We talk about a slush fund as being a bit of money left over to buy fripperies or luxuries, etc. And the slush here was actually the liquefied fat that was left over from rations on board a ship, and it would be quite useful for candle making, etc. So when sailors came ashore, they would take this fat with them and sell it off and get some money for it. And that slush got them some money for rum and various things. So that was their slush fund.

HZ: Wow, okay. When the nautical slang is true, it's really good.

SUSIE DENT: Yes. When it's not, it's just annoying.

HZ: ‘Bonanza’: that was another word that I did not realize had a maritime related origin.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, I associate bonanza with a really bad - well, not really bad, it was actually really good, but… was it a Western? Did you ever watch this? It had a good theme tune and it was set in the Wild West. But ‘bonanza’ is from the Spanish for fair weather.

HZ: The etymology of ‘bonanza’ is, I think, a portmanteau, because the word came to Spanish from Medieval Latin 'bonacia' - 'bonus' meant good, 'malacia' meant calm sea from the Ancient greek for softness, μαλακία. Put bonus and malacia together and you've got bonacia, fair weather at sea.

SUSIE DENT: And so it meant prosperity, but also it's associated with gold mines. because a bonanza was a really highly profitable mine. And that's another really rich - sorry to make a terrible pun here, but it offers a rich seam of material. But it's given - we have digs as in accommodation, that goes back to the diggings that grew up around gold mines, the accommodation and stuff. We've got panning out, which is like sort of sifting through the earth to find little nuggets of gold. We have so much that comes from that time.

HZ: ‘Derelict’ is another maritime law word I did not know. And that is property that has been abandoned on navigable waters without hope of recovery.

SUSIE DENT: And in some ways it's not really lost that sense of something that is forsaken, really. But yeah, it was particularly of a vessel that was abandoned at sea, and it goes back to a Latin word to completely abandon or forsake.

HZ: Like the word 'derelict', flotsam and jetsam are words with specific meanings in maritime law concerning who owns property after shipwrecks.

SUSIE DENT: ‘Flotsam’ is from the French flotting meaning to float. So it's essentially, stuff that you will find that is not deliberately thrown overboard, but that you will find, say, after shipwreck for example. And ‘jetsam’ is from the French jetér, meaning to throw, so it is thrown overboard in order to lighten the load of a ship in distress.

HZ: Granted, I don't have much business with the laws about who gets to own what they found in the sea, but I only ever hear flotsam and jetsam used in a non-specific sense of sea debris, and I never hear flotsam and jetsam independent of each other.

SUSIE DENT: So yeah, they didn't always go together. And in some ways I think they've joined each other under the same umbrella because they both involve stuff that you will find floating on the sea as debris.

HZ: There's a whole other term that goes with them too, lagan, which refers to stuff that sank, and is sometimes tied to a buoy so it can be recovered later and restored to its rightful owner. But lagan doesn't get to be part of the flotsam and jetsam party, some words are just left behind on the sea bed. Like the lost positives, the absent partners of Susie's beloved orphaned negatives. Orphaned negatives are words like gormless - what happened to gorm? Ruthless but no ruthful? Uncouth not couth? Nonplussed but no plussed? Disgusted but not gusted? Disgruntled no gruntled? Feckless not feckful?

SUSIE DENT: I think ‘ruthful’ is my absolute favourite because if we're full of compassion we're ruthful; but no, we just want to be ruthless. I'm still on the lost positives mission to bring those back, because I'm always finding new ones: as I wondered the other day, can you be mayed as well as dismayed? And of course you can, because ‘may’ is there as a verb.

HZ: I'm just looking at dismay and I'm sort of confused that the French root for the ‘may’ part also means to trouble or disturb so what's the ‘dis’ doing?

SUSIE DENT: Okay, well it might be an intensifier.

HZ: The French don't do double negatives!

SUSIE DENT: Well, exactly. To dismay. To discourage, yes, you're right. But then if you look at may, as a verb, expressing objective possibility, obviously, but yes, you're right, can also mean to dismay, which is very confusing, or to take part in the festivities of May Day. That's the thing about the dictionary: you will always find yourself contradicted at some point in the 16th century or whenever it was. And everything we've been arguing about now, whether it's disinterested and uninterested, we've been arguing about for 400 years.

HZ: Nothing new under the sun.

SUSIE DENT: No. That's from the Bible, isn't it, that one?

HZ: Is it? They probably stole it from someone else.

SUSIE DENT: Probably. It's probably a cover version.

HZ: Some of these words, like ‘discombobulate’, never had a positive counterpart - although it's never too late to get one!

SUSIE DENT: If you go to Mitchell Airport in Milwaukee, you can go through a recombobulation lounge. I really like that. I don't know who invented it.

HZ: Who invented it? Barry Bateman, the now retired director of Mitchell Airport. ‘Recombobulation’ won the American Dialect Society’s most creative word of 2008. He came up with the recombobulation areas to add a bit of comic relief to the often trying airport experience and to give passengers a place to collect themselves, put their belts back on, put their electrical devices back into their bags, after they’ve been through the security scans.

SUSIE DENT: You go and you gather your spirits and your luggage, and you recombobulate. I love that.

HZ: Inept but not ept, unkempt but not kempt, unruly but not ruly - why did English only retain the negative side not the positive?

SUSIE DENT: I wish I had this very simple, anthropological answer to this one, but the only thing I can think of is that we've always been a pessimistic lot, and I'm talking about English speakers in and not necessarily just the British, and because we're quite gossipy as humans, and we tend to gossip about even in a teasing way, about sort of unpleasant things, I think we just do like to dwell on the sort of slightly unpleasant side. Even if it's a kind of dark, sort of sardonic humour, I think we do like to dwell on that side of life. And at a guess I would say insults outweigh compliments in the OED by about 5 to 1.

HZ: Maybe - just trying to put a positive spin on it - maybe people assumed that the positive was the default and that's why you didn't need words to explain it as much as you needed ones that deviated from the happy default. Tenuous?

SUSIE DENT: I know, but where's the happy default gone because? We just don't, we don't talk about it anymore.

HZ: What for you is the bigger picture in all this work? There's all these, like, tiny little fascinating avenues to go down. But when you're looking at the whole map, what does it mean to you?

SUSIE DENT: Hmm. That's a really good question. And if I'm completely honest, I feel like I don't have an eye on the destination. And I hate to use that cliché, but it's all about the journey. But I get so fired up by all the sort of little rabbit holes that I fall down that actually I don't often look up and think, "This is what needs to happen." I have a wish that some of those words that are languishing - not just the lost positives, but so many others that have fallen of use that I cannot explain why - that they will come back slightly. So if there's a few things I can do to bring those back, I would be very happy. I think I, like every other lexicographer, can keep championing the importance of evolution and to put people's mind at rest that English is not either heading for the hills or going to the dogs, either of those.

HZ: What if the dogs are on the hills? Then they can do both.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, exactly. No, the Golden Age has never existed and it's not in the past. It may not be in the future either. It's a messy thing, but I think we can just keep embracing it. So the bigger picture is just a very subjective one of keep doing what I'm doing and keep loving it. So, yeah, no lofty ambitions. I just hope that I can keep doing this for as long as I enjoy it. And just concentrating on good things was actually maybe bearing out what Lisa Feldman Barrett, that psychologist, actually said, which is that you begin to feel it yourself.

HZ: And one of the many nice things about these words that are joyful is that they're free to use.

SUSIE DENT: Yes!

HZ: Open to everyone.

SUSIE DENT: Yes, I wish I could copyright them and then I would be very rich.

HZ: Maybe that's why people skewed negative: someone copyrighted all the happy words and people were like, “Alright then. All we've got is despair now.”

SUSIE DENT: That would be amazing. That sounds like - tather than the Childcatcher of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, it sounds like somebody, the Wordcatcher, who goes around - that would actually make a great kid's story - who takes away all the positive words, and imprisons them, and then the heroes have to go and release them. Should we write it?

HZ: Yeah. Let's get on it.

SUSIE DENT: I'm going to spend the rest of the day thinking about a title for it.

HZ: Get your illustrator on the phone. This is gonna be big.

SUSIE DENT: I will.

HZ: While you wait for our incredible book to hit the shelves and the inevitable screen adaptation and stage musical of the film and screen adaptation of the stage musical, check out Susie’s latest books: Interesting Stories About Curious Words and Roots of Happiness: 100 Words for Joy and Hope. You can also hear her on an earlier episode of this show, To Err Is Human, where she talks about how mistakes get lodged in language.

Music alert: my multitalented friend and cohost of one of my other podcasts Veronica Mars Investigations, Jenny Owen Youngs has a new album out, Avalanche, which contains the first song I ever heard her play, when we met a few years ago at a podcast event, and the one song was enough to convince me, yes, I’ll commit murder for this person. You can try to guess which one when you listen to Avalanche, which is out now in the musicplaces and Bandcamp and Spotify and very cool purple vinyl - I don’t have a record player any more but it’s tempting to get one again for the purple vinyl. Jenny’s also going on tour in the USA this autumn, so check for dates in your vicinity at jennyowenyoungs.com.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

spifflicate, verb, informal/humorous: destroy or defeat utterly.

Try using ‘spifflicate’ in an email today.

This episode was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman, the music is by Martin Austwick of palebirdmusic.com and the podcasts Neutrino Watch and Song By Song.

Our ad partner is Multitude. If you have a product or thing about which you’d like me to talk, sponsor the show: contact Multitude at multitude.productions/ads.

Seek out @allusionistshow on YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, Bluesky, the ghost of Twitter past… And you can hear or read every episode, find links to more information about the topics and people therein, donate to the show and become a member of the Allusioverse, and see the full dictionary entries for the randomly selected words, all at the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.