Listen to this episode and find more information about the topics therein at theallusionist.org/rhino.

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, interrupt my planned podcast because there’s breaking news - as in news of everything being broken. This episode isn’t about current events, but is somewhat inspired by them: because the specifics change but the chaos is perennial, or so it seems.

Content note: there are descriptions of torture about halfway through.

On with the show.

Today we’ve got three political eponyms.

Ira Glass voice:

Chapter 1: Cacareco.

In Brazil, a ‘voto cacareco’ is a slang term for a protest vote. Aptly, ‘carareco’ means a useless object or an old worn-out thing, sometimes a trinket; but that’s not what the term is referring to: it’s an eponym, although Cacareco was named after the word because of her supposed resemblance to rubbish when she was born. Look, it’s just unfair to judge anyone on their appearance at birth, there’s everything to play for after that.

Cacareco lived most of her life in Rio de Janeiro, but it was São Paulo that put her name into the political lexicon. In 1959 she was seconded there for a few months, and during that period, city council elections were held. And the 3.7m citizens were very disenchanted with their corrupt politicians and the mess the city was in. Prices had been soaring, there were food shortages, the roads were a mess and sewers were overflowing - imagine! (Don’t need to imagine, it’s happening.)

Despite there being a whopping 540 candidates to choose from for 45 council seats, people decided to add one more: Cacareco became the write-in candidate of choice. The way the voting worked was that members of the electorate each had an envelope into which to put the ballot paper of their chosen candidate - that year it was quite a popular move to put a black bean in the envelope, to protest the shortage of beans, albeit by further depriving oneself of a bean. But an even more popular move was to put Cacareco into the polling envelope, so popular that Cacareco received more than 100,000 votes, winning by a landslide, the next closest candidate only got 10,079 votes - of the eleven political parties running, even the biggest couldn’t beat Cacareco with their cumulative 95,000 votes.

So what’s the problem? Cacareco was only five years old.

And she was a rhinoceros.

Cacareco had been sent on loan by her home zoo in Rio to be the star attraction at the newly opened São Paulo zoo. She was just there to eat vegetables and snooze and be looked at, yknow, do rhino-in-a-zoo stuff; her swerve into politics was unexpected. But not unprecedented. Cacareco was not the first non-human animal candidate for public office, and certainly not the last. Four years earlier, in another Brazilian city, a goat had won an election - and it wasn’t even the first goat to win an election in Brazil. In many countries there have been creature candidates including cats, gerbils, sheep, crawfish, chimpanzees, gorillas, turkeys, cockatoos, roosters, dogs, so many dogs; and pigs - including Pigasus who was running for the US presidency in 1968, Pigasus was arrested at a rally and Richard Nixon went on to win that election.

Let’s not even get into the inanimate objects that have been electoral candidates, such as the foot powder that was elected mayor in the town of Picoazá in Ecuador in 1967.

Animals are joke candidates, but it’s not animal politicians that make politics a joke. When human politicians are a joke, it’s not the laughing kind.

As Cacareco’s supporters said during her campaign: "Better to elect a rhino than an ass." But it might be better to elect an ass than a human. A mule named Boston Curtis did win for Republicans in 1938 in Milton, Washington, a prank by a Democrat to prove the voters didn’t care about knowing who they were voting for or what their policies were - the mule didn’t even have any policies. It’s a mule!

Despite winning the election so resoundingly, Cacareco got Boaty McBoatfaced and was not allowed to take office on the São Paulo council, and I’ve read differing accounts for why: she was not a resident of São Paulo; she was already back home in Rio by the time of the election, possibly bundled back there as part of a coup against her political ascendency; possibly snatched back by Rio, peeved that another city was laying claim on Rio’s special rhino; or was São Paulo just bitter about this rhinoceros-shaped insult to their democratic offerings. A week after the election, São Paulo held another, and a human won - if you can really consider it winning if you already know that people preferred to vote for a rhino than you, a rhino whose zookeeper described as having a brain that would fit in a brazil nut.

Cacereco continued to be added to more bills in elections, and was beaten to the student presidency of the University of Havana by the Cuban revolutionary Rolando Cubela. But in 1962 she died of a liver problem, aged only 8 years and eight and a half months, young for a rhinoceros.

Her legacy: she inspired the founding of the Rhinoceros Party of Canada in 1963, which for decades ran on joke policies like repealing the law of gravity and paving the province of Manitoba to make the world’s biggest parking lot.

And Cacareco is memorialised in Brazil’s eponymous expression for a protest vote: voto cacareco, when the human politicians have failed so much to be appealing, you’d rather vote for a rhinoceros. The rhino won’t fix the sewers either, but she’s not going to use her powers for evil, rhinos are chaotic neutral.

Chapter 2: Guy

HZ: This is a piece that was on the show a few years ago, about the origins of the word ‘guy’, from Guy Fawkes - tis the season, with 5 November, Guy Fawkes night, impending. And to explore the complex and fascinating history of the word, I was joined by historian Victoria Buckey and longtime eponym fan Roman Mars.

HZ: Do you know anything about Guy Fawkes, as an American?

ROMAN MARS: I do. Yes. The Gunpowder Plot. I know at least the edges of that story as somewhat reinforced by (I'm sure completely historically accurate) V for Vendetta. But yeah, I know Guy Fawkes and I know what a Guy Fawkes mask is. I had no idea that Guy Fawkes predated the use of the word 'guy' as a general person.

HZ: No, I didn't either. When you grow up in Britain, you don't know a lot more than you do as an American who had V for Vendetta. What you know is that on 5th November there are fireworks displays everywhere, and in some places they'll still have a bonfire and they'll burn a guy on it which is an effigy of a human named after Guy Fawkes who, in the early hours of 5th November 1605, was arrested for the Gunpowder Plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament.

ROMAN MARS: Wow.

HZ: So this general word for person that we have now came from an effigy which came from a specific person.

ROMAN MARS: That’s amazing. That’s amazing.

HZ: Get ready for a concentrated dose of 16th and early 17th century English history.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: It was Henry VIII, basically, who wanted to get together with Anne Boleyn. At that point England was entirely Catholic. And Henry VIII wrote to the Pope and said, "I want to get divorced; I want to get together with Anne Boleyn," and the Pope said, "Absolutely no way; that's not happening." And Henry VIII went, "Well, I'll just start my own church then."

HZ: That’s historian Dr Victoria Buckley. And the church King Henry VIII started was the Church Of England, which retained some of his favourite bits of Catholicism but allowed him to get out of his first of six marriages. This was known as the Reformation, and in 1534, England officially separated from Rome - bye, Pope! Hello, centuries of religious and political turmoil!

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: What happened was that England became a country that was kind of divided between those people who subscribe to the new Protestant faith, and Catholics who adhere to the old way of doing things.

HZ: Monasteries and convents, of which there were 900 around England, were dissolved, their property and money seized, their religious artefacts destroyed. Catholic practices like confession and praying to the Virgin Mary were banned. The pendulum oscillated during the reigns of Henry VIII’s children, veering more Protestant under Edward VI, back to Catholic under Mary, then away again under Elizabeth I, who couldn’t endorse Catholicism because, by its tenets, she was Henry’s illegitimate child, being the product of his controversial second marriage, and therefore could not be a legitimate occupant of the throne.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: And under Elizabeth I - she was essentially a Protestant queen, but she had maintained a lot of Catholic ideas.

HZ: She wasn’t sympathetic to Catholics, though. Very soon after she took to the throne, a law was passed making it compulsory to attend Church of England services. Under threat of fines, imprisonment or execution, Catholics had to worship in secret. After a 44-year reign, Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, and King James VI of Scotland travelled south to become King James I of England.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: And there was a lot of disgruntlement because he was a very very very staunch Protestant.

HZ: The Gunpowder Plotters certainly weren’t pleased. They wanted a Catholic monarch, or at least a monarch who was tolerant of Catholicism. Add that to the clutch of reasons that have been offered for their plot.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: Part of it, I think, was the idea of notoriety. Part of it was the idea of making a big splash. They were quite interested in just political change for its own sake; and they also were a bit disgruntled. But above and beyond that, they wanted to restore the Catholic religion. They wanted to get rid of James I. And if their plot had been successful, they would have blown up the Houses of Parliament which means they would have blown up the King, they would have wiped out the judiciary, the clergy. It would have effectively decapitated the head of the ruling body in England.

HZ: The Gunpowder Plot started being plotted around the end of 1603, start of 1604, by a man in his early 30s named Robert Catesby. Several members of his Catholic family had been imprisoned or fined for their faith. First, he recruited his cousin, Thomas Wintour, and then John Wright and his brother-in-law Thomas Percy.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: And then they realized they're going to need quite a lot of other people in the group. So they dispatch someone overseas to the Netherlands, where England was at war with Spain. And that's where they met Guy Fawkes.

HZ: Guy Fawkes was English, but as a Catholic he had been fighting on the side of the Spanish for the previous ten years.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: He was a really, really well-respected captain, and he was very devout. But he was known as an ordinance man, so his expertise was in laying wires, the gunpowder and stuff like that.

HZ: In the end, there were thirteen plotters altogether. Several of them had been involved, along with Catesby, in the thwarted 1601 Essex Rebellion against Queen Elizabeth.

Back in London, in March 1605, they rented a vault beneath the Houses of Parliament, and hid 36 barrels of gunpowder in it. They planned to detonate on the day of the State Opening Of Parliament, which was set for 5th November 1605. But then…

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: What was known as the Monteagle letter was sent in October 1605. Lord Monteagle was a famous Catholic, and someone tipped him off. And it basically said, "Don't go to Parliament on 5th November, because you'll be blown to smithereens."

HZ: Nobody’s sure who wrote that letter to Lord Monteagle. But King James I sent people to search for signs of trouble. On the night of 4th November 1605, the eve of the planned plot, Guy Fawkes went to the vault to check on the gunpowder, to make sure everything was ready to detonate the next day. Unfortunately for him, the keeper of the precinct of Westminster was poking around beneath Parliament.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: And he went into the vault; and there of course he found Guy Fawkes, clutching a lantern and a box of matches or a tinder box.

HZ: In the early hours of 5th November, Guy Fawkes was arrested, and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: And then, on the 7th of November, Guy Fawkes was tortured in the Tower. He was manacled, which involved his hands being put into iron manacles and then suspended from the stone wall, and underneath his feet was like a pile of firewood. And then very gradually they kicked bits of the firewood away so he was effectively suspended by his wrists. So his wrists were both broken. And then they racked him on the rack. All his joints were effectively completely dislocated and broken. Because he had been so badly tortured, he started naming loads of names and spilling the beans.

HZ: While Guy Fawkes was being tortured in the Tower of London, what about the other plotters? Well, they were already nowhere near. When word got around about the Monteagle Letter, they had fled London, and were hiding 130 miles away.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: They all holed themselves up in this house called Holbeche House in Staffordshire. And they were all lying around going, "Ooh, a narrow escape." And they were drying some gunpower by the fire, and it exploded, in a really ironical way. And they all a lot of them went, "Oh God, that's divine intervention," and they all fled from Holbeche House. But then the authorities caught up with them and there was a huge siege, and a lot of the plotters then were killed in this siege; they were shot in this siege.

HZ: The surviving plotters were taken to the Tower of London, and at the end of January 1606 they and Guy Fawkes were publicly executed.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: And they met the most awful end. They were hung, drawn and quartered, which effectively meant being hung by the neck until you were almost dead but not actually dead. Then you were cut down then, all your organs were cut out, and set fire to before your eyes. And you were eventually kind of dispatched on a butcher's block. And that was that was the penalty for treason. That served as not only horrendous punishment obviously, but it also served to deter people who were thinking, “Well maybe I'll commit a bit of treason against the king,” or “Maybe I'll get involved in a plot.” Because executions in that period were huge spectacles, a bit like theatre: people went along to have a good look at what was happening and to watch people going through all of this awful, slow, butcherous method of being killed. And it was public theatre.

HZ: And it soon became a public celebration as well. A couple of months after the foiled plot, an act of Parliament was passed that actually made it law to to celebrate Gunpowder Treason Day every 5th November, to give thanks for the “joyful deliverance of James I” from the Catholic plotters. And even though that law was repealed in 1859, towns and villages all over England still mark 5th November each year with fireworks and a bonfire. Why a bonfire?

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: Well, bonfire was part of the Protestant tradition: people would light bonfires in the street in order to celebrate things. For example, when James I came to the throne, people lit bonfires and it became quite standard practice to celebrate in the street with fires and stuff like that.

HZ: And in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot, anti-Catholic sentiment was even more virulent than it had been before, so people would chuck onto the bonfires effigies of the Pope or the devil, and then, in time, of Guy Fawkes.

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: In the 18th century, Guy Fawkes started to become synonymous with bonfire.

HZ: In the run-up to Bonfire Night, children would wheel around their Guy Fawkeses, asking for money. “Penny for the guy!” Eventually the bonfire night effigies came to be of other hate figures - the town of Lewes in East Sussex keeps up the tradition each year at its particularly enthusiastic bonfire night events with a topical choice, such as, in 2015, the then Prime Minister of Britain David Cameron with a pig’s head. Google it.

But somehow, Guy Fawkes’s name is the one that became attached to the effigies - by the early 19th century, they were known as 'guys'. And then, by the 1830s, the word ‘guy’ meant a scruffily dressed person, either in reference to the state of the effigies, or of the people who were begging with them. By 1847, ‘guy’ was an informal term for a male person - in American English. So somehow the word crossed the Atlantic, and took on a new meaning, forgetting the connection to a political plot more than two centuries before.

ROMAN MARS: That's interesting.

HZ: You innovated.

ROMAN MARS: Yeah.

HZ: You took that meaning out and you gave that word to everyone. I'm treating you as a representative of your nation.

ROMAN MARS: Thank you. That is remarkable.

HZ: But is it fair that, out of the thirteen Gunpowder Plotters, Guy Fawkes is the one who is remembered in this way?

VICTORIA BUCKLEY: No, not at all. Because the poor man, really, he wasn't the ringleader. He was only brought in to do the ordinance stuff; he was just a very small cog. But because he was the only one that was initially captured, he's the one that's now representative of the whole thing. So he's now the big bad bogeyman. And that's been consistent since 1605. But it's only because all the others fled the scene and left him to carry the can, effectively. The real person that we all really ought to be thinking of as being the person that's ultimately representative of the plot is Robert Catesby. He was the mastermind, he was the one who dreamt it all up, he was the one that raised all the money, found all the ammo and organized everything and found the vaults and sent people overseas to agitate in the Netherlands. He really was the ringleader, whereas Guy Fawkes was just a bit of a beard that happened to be caught with his matches in his pocket.

HZ: This eponym though: I'm wondering whether it partly caught on because it's such a small word - three letters, and it's basically a consonant and a breath; and therefore it's easy to assimilate and it's easy to use often. So I'm wondering whether some aesthetic of the word made it common - because it could have been so different. Guy Fawkes didn't go by the name 'Guy Fawkes'; it was his birth name, but the name he went by was John Johnson, and johns isn't such a general term for people; it means something specific.

ROMAN MARS: Yeah, it does! Yeah, it is more specific... That's interesting.

HZ: It’s another ‘gentleman’ term.

ROMAN MARS: It's a family show!

HZ: And then he styled himself ‘Guido’ because even that was a more Spanish version of guy he'd been fighting on behalf of the Spanish for the best part of a decade.

ROMAN MARS: Yeah. So we could say a bunch of guidos, essentially.

HZ: But that term has a meaning as well.

ROMAN MARS: It does, yeah; I would say that it would probably be a slightly derogatory epithet for a group of Italian-Americans or something like that, you call them guidos. Not you, someone.

HZ: I wouldn't, but I’ve only seen it in the context of people commentating upon Jersey Shore, which I have not seen.

ROMAN MARS: Yeah, I think that's my sense of it. But I've never seen it or probably heard it used beyond what was on television.

HZ: And then we could have had robert catesbys. Roberts.

ROMAN MARS: Yeah. Catesbys would never... I think you're right in the sense that the shortness, as a phoneme, ‘guy’ is really satisfying. Catesbys and roberts wouldn't work; guidos wouldn't work exactly. But I still find it kind of amazing that you would have this the idea of this effigy becoming a general term. It's weird that an enemy of the state that is burned in effigy would take on such an anodyne moniker - that the evil of that wouldn't transfer. It's like calling people like a group of people a bunch of Hitlers. “Hey Hitlers! How's it going?”

HZ: “Hey Osamas!”

ROMAN MARS: Exactly. You just can't picture it with any other terrorist. And having any of the morality sort of leached away from it is kind of stunning. You'd think that would be the thing that would be retained in the meaning is the plot.

HZ: Or the divisive history wrapped up in it. Because on the one hand, you have people who call Guy Fawkes a terrorist, a Catholic terrorist. While on the other, you have him being the unfortunate figurehead of an attempt to agitate politically on behalf of the oppressed Catholics.

ROMAN MARS: If the meaning wasn't you know transferred for this long and lost and at a certain point, you just have to let it go, because everything has horrible origins.

HZ: Yeah. A lot of words in our language have, in a metaphorical sense, a man lurking beneath them with a load of gunpowder and some matches.

ROMAN MARS: Exactly!

HZ: One more eponym to go. Coming up next: bork.

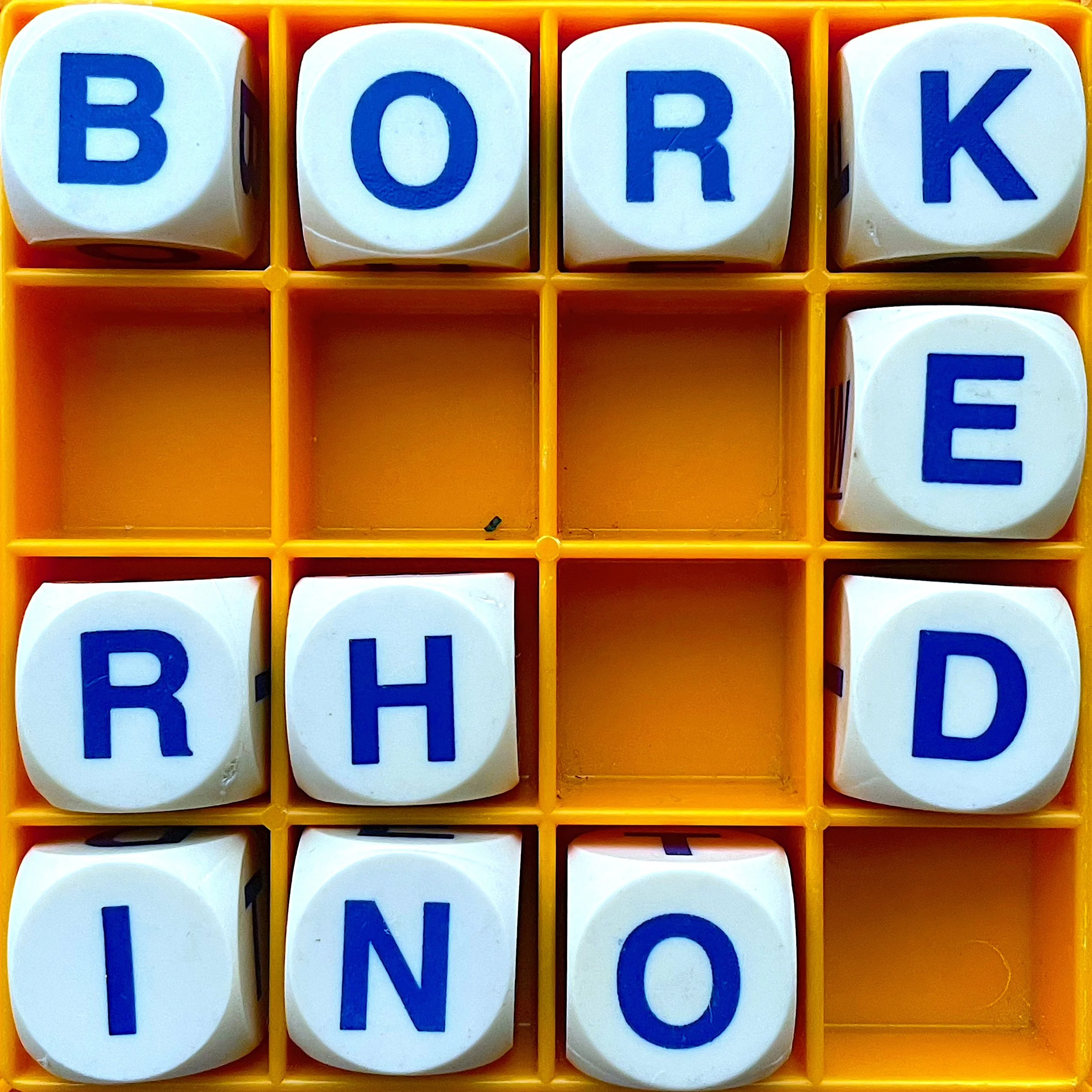

Chapter 3: Bork

HZ: This show is such an education for me: until I looked it up yesterday on one of my daily etymological strolls, I did not know that ‘bork’ was an eponym. Maybe not in all its uses, like DoggoLingo a wry respelling of ‘bark’, or in the mouth of The Muppets’ Swedish chef where it’s a gibberish word. Computer’s borked - probably a deliberate mispelling of ‘broken’, but possibly an eponym from Robert Bork, the American judge twice thwarted from being appointed to the Supreme Court.

A lot of political eponyms are fairly straightforward, using the name to label an ideology, like Maoism or Leninism or McCarthyism. But a lot that have come up quite a bit on the show before were more oblique and often disses like silhouette, chauvinism, quisling and gerrymander - it’s so often not the legacy the eponymous person might want, but they rarely get the choice. Trying to get language to do what you want is like trying to get a cat to take medicine.

I’d heard of the term ‘bork’ but I hadn’t heard of Robert Bork, just like I hadn’t heard of Russian politician Vyacheslav Molotov after whom molotov cocktails were named, in a bit of satirical eponymy coined by the Finns during the Soviet-Finnish War of 1939. Molotov was the Soviet foreign minister at the time, second in command to Joseph Stalin, and Molotov’s breadbaskets was the Finnish nickname for the cluster bombs being dropped on them - so-called because supposedly Molotov had said on state radio that these were not bombs but food aid packages. This bit of propaganda might itself have been propaganda, but since the Finns were the ones getting things dropped on them, they get license with the jokey name, and also gave it to the improvised incendiary projectiles they were lobbing at Soviet tanks, the molotov cocktails, a drink to go with the bread. They’re officially called things like ‘bottle bombs’ or ‘burning bottles’, more descriptive but it’s so often the case that eponyms stick even though all they tell you on the surface of it is that a person has been invoked.

And so, to Bork. Merriam-Webster defines it as: “to attack or defeat (a nominee or candidate for public office) unfairly through an organized campaign of harsh public criticism or vilification.” It’s not so far away from the computer type of bork, both suggest brokenness beyond repair. Borkenness beyond repair. Like Robert Bork’s chances of getting appointed to the Supreme Court.

In 1973, Bork had had a sniff of that Supreme Court seat - not literally as far as I know, I’m not trying to imply anything. The then-president Richard Nixon had promised him the next available place, as a reward: Nixon wanted Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox to be fired, and the Attorney General AND the Deputy Attorney General had refused to do it and resigned in protest. Who’s next in line to sack Archibald Cox? Solicitor General Robert Bork, and he did do it, he fired that man. But then Bork didn’t get his reward of the next Supreme Court seat, because before one became available, Nixon’s presidency was borked. In the computer sense.

And when a seat did open up in 1975, during Gerald Ford’s presidency, civil rights groups protested against Bork being nominated, given his record of, for instance, in 1964 opposing a law to require restaurants and hotels to serve customers of all races, or in 1965 opposing the abolition of a ban on contraception for married couples. Bork was a staunch originalist, meaning if something wasn’t enshrined in the Constitution - original version, not updated - Bork wasn’t a fan of it, that included privacy, feminism and the sexual revolution. So Ford decided not to nominate him for Supreme Court, but considered making him director of the CIA, but decided he was too unpopular for that too.

Bork went back to teaching law and being a judge, then in 1987 that Supreme Court seat came within sitting distance again, when Bork was added to the list of potential nominees for Ronald Reagan to consider. Joe Biden had been amenable to Bork’s possible nomination when it was mooted a year earlier, but now told Reagan, “If you nominate him, you’ll have trouble on your hands,” and turned out to be right: Reagan did nominate Bork - and the eponymous borking started. Almost immediately, in fact: a mere 45 minutes after Bork’s nomination, Senator Ted Kennedy made a televised speech which included the statement:

[Clip of Ted Kennedy’s speech in the Senate:]

Robert Bork's America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, Blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, and schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists would be censored at the whim of the Government.

In the political climate of 2022, this would not bork Bork at all, it’d probably work in his favour, although Bork did say, “There was not a line in that speech that was accurate.” I’m not the one who will pick through the debris of Bork’s voting records to determine what his political preferences really were in practice, but wherever there is uncertainty, whenever there is contradiction, there is the opportunity for any side to stick in a crowbar and crank it wide open to let a whole load more in.

Civil rights groups and left wingers could say that Bork was in favour of segregation and anti-contraception and the right wing could say that’s a lie. Bork could say that the opinions he had espoused in the past wouldn’t affect his choices as a judge, but nobody could know whether or not that would turn out to be true. A partisan brawl waged for weeks: Bork’s nomination gave the Republicans an opportunity to get more conservative lawmaking, and the Democrats fought to prevent it. A particular concern for the left was that Bork would overturn Roe v Wade, and that’s one point that the right agreed with, he probably would.

Bork did not get that seat on the Supreme Court. The Senate vote on him was the third worst defeat on record. And people said that Bork had been borked by disinformation, propaganda, false claims of racist sexist principles; but Bork may have been borked by Bork, by the dour way he represented himself and his originalist views during the twelve days of confirmation hearings, presided over by Joe Biden who ended his own presidential campaign partway through them, another thing borked.

The term ‘bork’ took off before the hearings even happened, and fifteen years later was added to the Oxford English Dictionary. As we know, language is not neutral, and the Robert Bork-derived meaning of ‘bork’ was popularised by Republicans, so it carried the sense of unfairness, a smear campaign. ‘Bork’ is another word that gets used to discredit criticism, even is warranted. So although ‘bork’ has two different origins, both of them eventually come to mean destruction, it’s just the eponym one comes with purposeful malevolence. Whereas computers don’t care! Computers only have the power we give them! Although that does go for humans too.

The Allusionist is an independent podcast pumping out that free edutainment, and if you would like to support this endeavour, recommend the show to somebody, I’d be most grateful. If you have some spare cash you can also help fund the show - go to theallusionist.org/donate, and in return you get behind the scenes info about the making of each episode, you get regular livestreams where I read from one of my many dictionaries and we chat about all sorts of topics: butter sculpture, leaf peeping, the etymology of plankton, and wolves made of chocolate. And you get to hang out in the Allusioverse Discord community, which is a lovely friendly corner of the internet - and aren’t those precious these days? Join us at theallusionist.org/donate.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

kype, noun: a hook formed on the lower jaw of adult male salmon and trout during the breeding season.

Try using ‘kype’ in an email today.

This episode was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman. Thanks to Julia Furlan and Caetano Galindo, and to Martin Austwick for the music. Hear his compositions via palebirdmusic.com and as Pale Bird on Bandcamp. Our ad partner is Multitude. To sponsor an episode of the show in 2023, contact them at multitude.productions/ads.

Find me @allusionistshow on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. And find every episode of the podcast in audio and transcript form, and the full dictionary entries for the randomly selected words, and links to the guests plus more information about the episode topics, all at the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.