Visit theallusionist.org/kinderegg to hear this episode and learn more about the topics therein

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, put on my language-suit, climb into the languagemobile and head out to clean up this city. By rubbing extraneous apostrophes off chalkboards.

This episode is about a warning, a dire warning, don’t ignore the warning, don’t throw away the warning without looking at it oh too late. Well, the warning tried.

By the way, if you want to know more about the making of these episodes, and to spend more time with your fellow Allusioneers as they have dubbed themselves, patreonise the show at patreon.com/allusionist and you get exclusive livestreams, behind the scenes intel and a Discord community, which is a nice place to hang out together.

Before we begin, I just need to state that this podcast is not affiliated with or sponsored by Ferrero or Kinder Surprise eggs. On with the show.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: So let's explain what a Kinder Surprise egg is in the first place.

HZ: Yeah. It's slightly bigger than a hen's egg.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's a foil wrapped chocolate egg, and it has an outer chocolate layer.

HZ: <shakes egg> I'm going to open it. I'm peeling off the foil, which is white and orange. And then we have the chocolate egg in two parts. I’m trying to split it without too much incident. And then inside that is a yellow capsule.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: The yellow being significant.

HZ: Is it?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's the yolk.

HZ: I never thought about that before, Keith! What have I been doing with my entire life?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Your whole life's been wasted.

HZ: And then inside the capsule:

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's a self-assembly toy.

HZ: It's a self-assembly toy. Let's not get distracted by that, because that's not even the true prize, is it?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: No, exactly. And you'll find at least two pieces of paper. Now, one of them is a sort of a picture showing how to assemble the toy.

HZ: That's right. And then the other one, which I don't know if I've ever even paid attention to before...

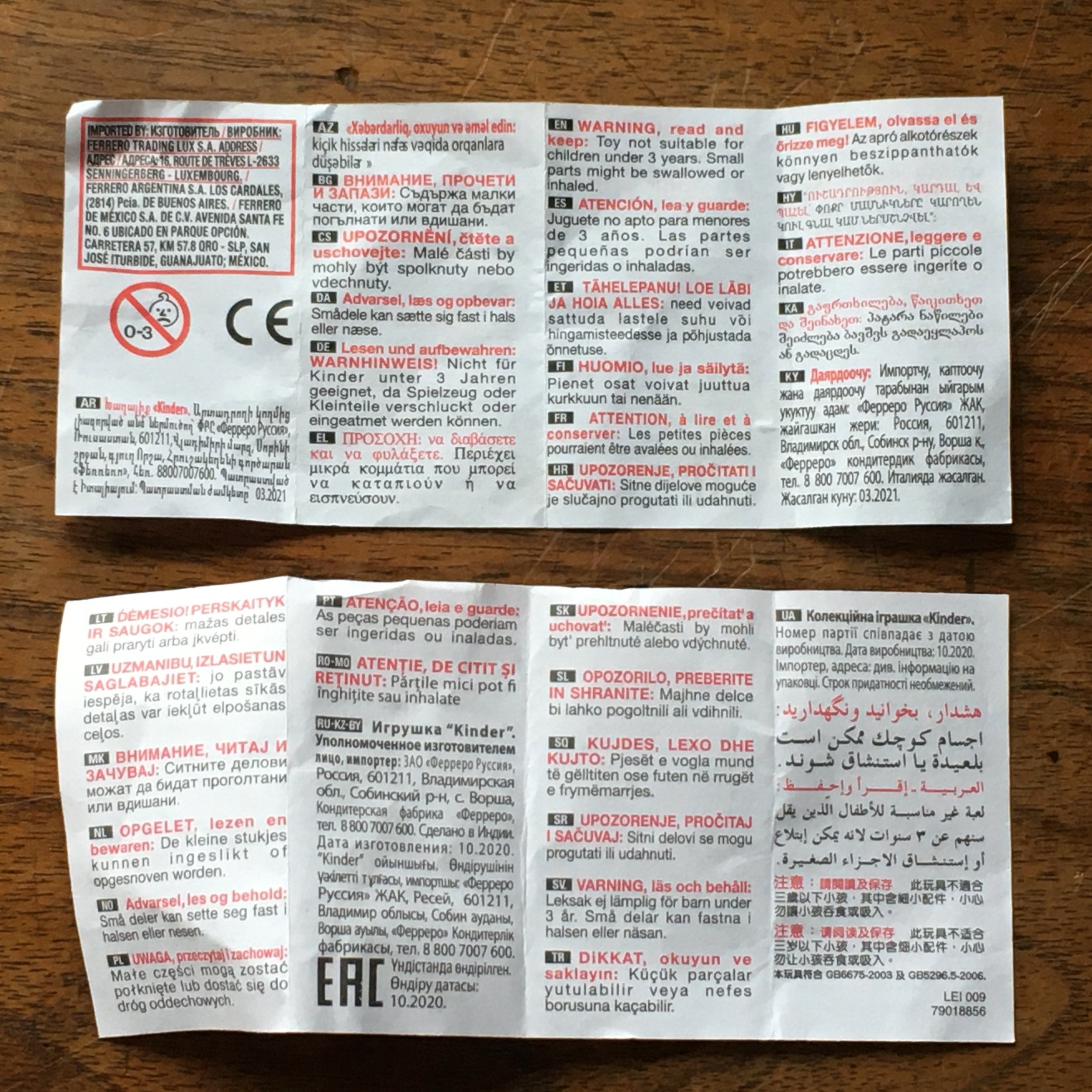

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's got the warning message, and it is in a literally dozens of languages on this tiny piece of paper. Why don't we read the warning message in English, if you can find it.

HZ: "Warning, read and keep" - that's in red, by the way - "toy not suitable for children under three years. Small parts might be swallowed or inhaled."

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: There you go. A message for the world, I'm sure you will agree.

HZ: Keith Kahn-Harris, a sociologist and writer, not only read and kept this message, he studied it and studied it and got it translated into more languages and eventually wrote a whole book about it, The Babel Message.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: The Babel Message is a book that celebrates the diversity of language, that takes as its starting point the piece of paper inside a Kinder Surprise egg, that features a huge number of warning messages in a huge number of languages.

HZ: How many languages? I'm trying to count.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: That's the interesting thing, because it's actually a more difficult question than you might imagine. So there are, for example, two Chinese messages, one of which is in traditional characters used in Taiwan and Hong Kong and Macau, the other one in simplified characters, which is used in the People's Republic. There are also things that look like warning messages, but are in fact not warning messages. So you get Ukrainian, Kyrgyz, Kazakh and Russian: it actually just gives the importer information and the date of manufacture, but there is no warning message in those languages.

HZ: So they just expect those countries to know not to swallow plastic toys,

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Maybe. But actually in fact, they have a warning message on the outside. There is always a warning message on the outer foil, but that only tends to be a one or two languages, depending on where you buy it.

HZ: If you’re listening in the USA, you're not allowed to buy a Kinder Surprise egg, warnings on the inside or outside are not enough.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Legally you cannot sell an edible thing with an inedible content.

HZ: Kinder Eggs, which have been manufactured by Italian confectionary giant Ferrero since 1974, breach the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act in the USA. You do get the Kinder Joy, but it's not the same. Kinder Eggs are also banned in Chile, albeit for reasons of not allowing a toy to be used as an enticement to buy foods with high sugar and fat content. A different sort of danger. But the Kinder Egg warning does serve a very important purpose - although you can't make people read or keep it.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Look, the whole thing is a contradiction, right? Imagine you are a multinational chocolate manufacturer.

HZ: Okay, wait, this could take some time to get into that mindset.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Imagine you work for one, that might be a little bit easier.

HZ: Even more implausible.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: You've got to do everything you can to make your product appeal to the target market, which is children, or rather it's actually adults buying them for children. So you've got to make them look fun and child-friendly, and their product packaging on the outside is very colorful, it uses sort of fun letters and stuff like that. On the other hand, you've also got to - and you actually legally have to do it in a lot of different countries, you have to warn them that don't give it to children under three, because it will kill them. And it actually has killed children under three. And it's actually killed children over three as well. I mean, not many, but it's happened.

HZ: More than none seems bad.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Because there are tiny little pieces. So it actually has a real purpose. But what they've got to do somehow is reconcile the marketing needs of making sure people buy the product with the need to warn against the product, or at least incorrect use of the product. So one of the ways that that is - and I'm not saying for a second that Ferrero being irresponsible here, it's kind of inevitable really - they want people to read it, but also in a way they'd rather they didn't, because obviously Ferrero don't want to kill people, obviously they don't, but it's a very strange thing that human beings do, to make something that is designed to be alluring and then say, "Don't do it."

HZ: But the contradiction isn't the thing that got Keith so interested in the warning message. It's that this tiny piece of paper contains the message in 34 versions, in order of appearance: Azerbaijani, Bulgarian, Czech, Danish, German, Greek, English, Spanish, Estonian, Finnish, French, Croatian, Hungarian, Armenian, Italian, Georgian, Lithuanian, Latvian, Macedonian, Dutch, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian/Moldavian, Slovak, Slovenian, Albanian, Serbian, Swedish, Turkish, Persian, Arabic, Chinese - traditional characters, and Chinese - simplified characters.

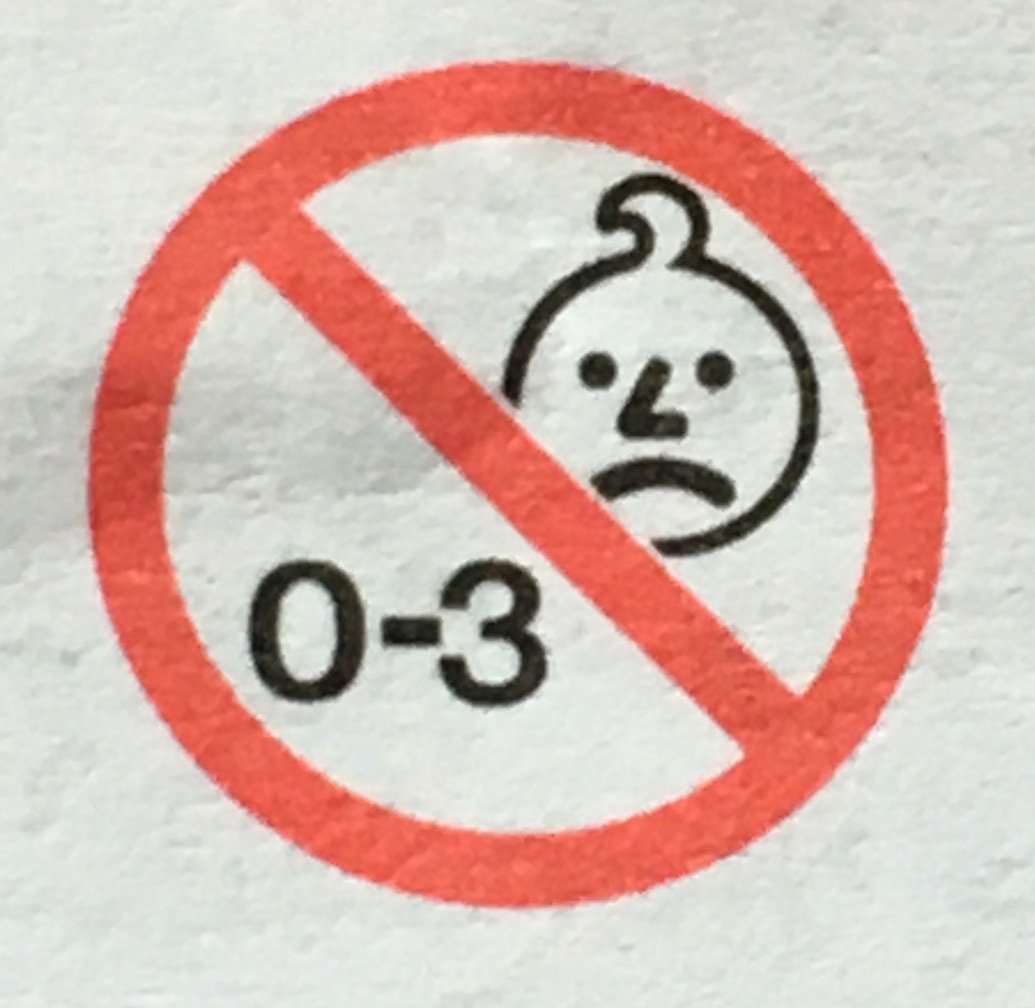

The warning also appears in non-verbal form: there’s a red circle with a bar diagonally across a cartoon of a displeased-looking baby’s face near the numbers 0-3. Well I’ve interpreted it to be a visual representation of the warning, but maybe not everyone would see the face and think "baby" or see the red stop sign and think "Don't let these little pieces of plastic toy near that aforementioned baby."

HZ: Of course, there is no universal communication system, not in language nor symbols, but the choices of languages that are on the piece of paper raise questions. Some absences are explicable - for instance there's no warning in Hindustani, the language with the third largest number of speakers in the world, but Kinder Surprise Eggs are not sold in India, just the Kinder Joys, and a speaker of Hindustani buying a Kinder Egg in another country would be assumed to be able to comprehend the warning in one of the other languages. Unfortunately Keith has never been get anyone who worked on the warning to talk to him about it, so all we can do is speculate as to why some languages are on there and some aren’t.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: The choices are very loaded and there are all of the EU languages on there, all the official EU languages except for two: Irish and Maltese. And the reason I think why they're not there is because it Ireland, uh, it's a minority language, even though it's an official language and it almost anyone who could speak Irish could also speak English.

And in Malta, Maltese is much more widely used than either did Ireland, uh, Irish in Ireland, but it's a largely bilingual country. So therefore they're defaulting to English, to a major world language when they can.

HZ: Keith found that was even more often the case outside of Europe.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Where they just seem to use major world languages, languages of colonialization, rather than localizing it. I got someone to buy me a Kinder Surprise egg in South Africa and you don't find Zulu or any of, I think it's 12 official languages there -

HZ: South Africa has eleven official languages, Zulu being the most commonly spoken as a first language; Engish comes in fourth. But it is the only official language of South Africa on the Kinder Egg warning.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Whilst this isn't exactly Ferrero's responsibility - well, arguably it's not their responsibility. One of the things that looking at that sheet does is it perhaps gives you a false impression of the complexity of linguistic diversity in the world. So for example, you look at that sheet and you think, ah, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian are three completely different languages; they must be completely different because there are three separate messages. But actually if you look at them closely, you'll see that Danish and Norwegian are very similar to the point of mutual intelligibility, at least in many different dialects, not all; Swedish is a bit more distant, but still very closely related to them.

The reason why Danish, Swedish and Norwegian are on there separately is because they're three different sovereign states. And so the reason why those languages are on there isn't because of any appreciation of linguistic necessity, but because of national laws and because of the histories of these countries that make them countries, which is not - I wouldn't say it's an arbitrary process, but it's not led by an appreciation of the linguistic reality.

HZ: What about, for instance, the countries that used to be Yugoslavia and now they are several separate countries with different languages?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: There's actually a website where scans of messages going back, warning message sheets go back about 30 years are housed. I call it ‘The Codex’ to try and give it some gravitas. You can actually track the collapse of the former Yugoslavia through the changing warning messages. The first one it appears is, is Slovenian. Then you get Serbian and Croatian, then later you get Macedonian. And of course there's Albanian because of Albania, but that's spoken in Kosovo as well, but you don't get Bosnian or Montenegran. Although I have found one warning message sheet where it, where it did seem to include Bosnian, but it was identical to what has always appeared as Croatian. Although linguists also say that the dialectical diversity within Serbia and within Croatian is actually wider than the difference between standard Serbian and standard Croatian. And it shows how the fact of having an official language is a statement of national identity rather than a statement of linguistic reality.

HZ: Do you know whether Ferrero have received protestations from people who are saying, “How come we don't get one when that has got one?”

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: No!

HZ: They're not going to tell us, are they? They're trying to stop children swallowing toys.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Ferrero have said very little - no, they've said nothing about the warning messages. And I did try over a period of years to talk to me about this and they have never responded and they are, as it happens, a company known for being secretive, not necessarily because they have anything horrendous to hide, but because they're still a family company, remarkably, one of the biggest family companies in the world. They don't necessarily have to report to shareholders. So they don't have to necessarily be as publicly accountable as they might be. Now they do do a lot of social responsibility stuff about things like palm oil, but when some random guy comes up to the rewards to talk to about warning messages, there isn't really any need to. But I've also found that evidence that no one is really reading these warning messages because I have found mistakes. And the fact that those mistakes are there suggest that no one is actually looking too closely.

HZ: Not even a proofreader?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: I'm sure there's a proofreader, but there is a major mistake in the Estonian one. Estonian has various diacritics; it has on certain vowels the tilde. Now the tilde looks like a little furrowed brow, it appears on top of an N in the word ‘España’. But on the Estonian message there they've used macrons rather than tildes; macron is a straight line, which is something that appears on certain languages like Latvian. They've also included an accent that does not exist in any language, a diacritic that is not in any language, that I could not reproduce on my computer no matter how hard I tried.

HZ: How did they manage that?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Well, it tells you they don't have a type setter working on the entire thing. It tells you that they've commissioned this from various translators across the world who've been sending it to some bloke in the Luxembourg corporate headquarters.

HZ: And he's hand drawing it?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: He must be, could be, seems to be manipulating images rather than typesetting everything, uh, because type setting, something like that is very, very difficult. There's also mistake in Azerbaijani as well.

HZ: What did they do?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: So they've created some ligatures, a ligature is where you put two letters together. So one, well, the most famous is in Danish where an A and an E are collided together.

HZ: æsc!

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Is that what it's called? Okay. But Azerbaijani does not use ligatures.

HZ: It does now.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It does now. Yes.

HZ: OK so there are some typographical mistakes and mysteries on the warning. But what of the meaning of the message? It has to be concise, because it's a small piece of paper with many languages on it; and it's as impersonal and dispassionate as...well, a corporate warning notice.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It has to be kind of God-like, and that is the nature of this kind of language. And one of the things I've thought about is, is that actually a bit self-defeating? Is there a way you could do it at a way that was a bit warmer because this is not how you would not say warning read and keep toys, not suitable for child under three years. You wouldn't say that if it was me saying, if, if you were giving it to your, I don't know if you've got three year old or two years, but if you did -

HZ: “Don't put that in your mouth!”

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Or I'd say to you, “Why on earth would you do something so stupid?” if I knew you really well, so there are a variety of registers.

HZ: That's when it too late, that's not preventative, which the warning is trying to be. Your child's already swallowed the toy by that point.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: So there is a question of whether actually official language really does what it is supposed to do. On the one hand, you might say something that is chilly and forbidding and authoritative might force people to pay heed. On the other hand, it lacks humanity,

HZ: I suppose any corporation trying to talk to people very concisely around the world is not necessarily going to seem the warmest.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: No, when they do it's fair to say that it's sometimes hugely irritating.

HZ: The English version is quite indirectly phrased. Did you find that with others of the languages?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Officialese in English often drops the direct article. It also often is in, uh the passive, it also misses out verbs, all sorts of things. It's very, very condensed, but if you compare it with the French, it doesn't seem to be able to do out do without those things as well as English can. And the same is true for the other romance languages, all of which include definite articles. Now I did do a wider survey to see which of the languages that could use definite articles - in other words, they have them, because not all languages do, Chinese doesn't for example - which languages that have definite articles and could use them on the message don't use them on the message. And unfortunately, I didn't really find the consistent pattern, which is another sign that -

HZ: That people have been involved.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: The people have been involved.

HZ: Different people.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Different people. But maybe also the officialese varies from country to country and draws on the grammatical possibilities or impossibility is that language in different ways.

HZ: But in English it says “small parts might be swallowed or inhaled” rather than "children might swallow or inhale small parts". So they've put it in the passive voice.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Yeah. But I think that passiveness is there to enhance the impersonal authority.

HZ: But also, three years is not the same thing in every culture, is it, because some cultures you're a year old when you've been born?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: That's true.

HZ: Which other concepts were the trickiest to translate? Because the more you look at this, the less unambiguous it becomes.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Well, ‘warning’, I realized at a certain point by research that the word warning is really, really weird, because it's almost like a tautology. would you put in a warning, "Warning"?

HZ: It's like "polite notice". Keith, if the notice was genuinely polite, you wouldn't have to say "polite notice".

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: I know, but the idea that you preface a warning with a thing saying this is a warning is a bit bizarre and may well be culturally specific, because there are quite a lot of languages there on the warning message sheet that don't use the word warning, they use, like in French 'attention' or in Spanish 'attención' or in Italian 'attenzione'.

HZ: 'Attention' is an act on the part of the reader. Whereas warning is an act on the part of whoever wrote the notice.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's almost like the imperative, but until I wrote this book, I didn't really think about how weird it was that we say warning, well we don't say it in fact, we very rarely say it.

HZ: Yeah. We would be more likely to say 'attention', wouldn't we?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Or 'take care' or 'watch yourself'.

HZ: 'Watch out!'

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: I like ‘watch yourself’. It’s a reflexive verb, and I like reflexive verbs.

HZ: Putting the responsibility back onto the person with the Kinder Egg toy.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Yeah, exactly. Although, you could say actually that the use of the word 'warning', which points to itself, maybe takes some of the responsibility away from the person, which may not be the intention. The intention is a kind of legal disclaimer, as much as anything else. But when you use the word 'warning', you're subtly reinforcing your responsibility rather than responsibility of the other.

HZ: That's why I think 'attention' is quite clever because that is immediately forcing the reader to engage and perform an act.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Except it sounds a bit odd in English.

HZ: "Atten-shun!"

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Yeah, it doesn't sound quite right. Whereas in French it does. And I can't really put my finger on why saying ‘attention’ doesn't sound quite right. It looks a bit better if you have a exclamation mark after it.

HZ: What about if it said "Oy!" exclamation mark?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: People might actually read it. There are creative ways you could get people to read it. And this is why research on this is so difficult. You'd have to have knowledge of 34 languages. What I don't know is how far linguistic necessity or creative choice was guiding these choice of words, where there other, do you talk about creative choice with a straight face? Because ultimately it comes down to a human being somewhere.

HZ: No language is neutral. Everything involves a choice, and a unpredictable human being -

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: - Is making that choice. There is an official European document, believe it or not, that gives recommended translations for wordings inside children's toys. And I don't know who came up with those. And sometimes the warning message sheet sticks with them, and sometimes it departs from them. So it's really a bit of a linguistic anarchy. And because there is nobody at Ferrero headquarters who speaks 34 languages fluently -

HZ: You said that they haven't been very forthcoming with you. So maybe there is, and you just don't know.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: This astounding individual who could speak 34 languages.

HZ: They have to protect them at all costs. Why this warning, are there any other products that compare?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Yes. They're not the only manufacturer of chocolate eggs with toys inside. And I've actually seen one, it's an Italian competitor. I can't remember who made it, that actually has 40 languages on it. It's got Icelandic on it.

HZ: Nice.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: So that's quite impressive. It's also virtually illegible, because it's even smaller than this one.

HZ: Oh, well this does have a tiny bit of wasted space around the little diagram of the child's face, but, yeah, not enough to get another six warnings on. This in several thousand years time, when the human race might be long gone, but perhaps the warning will be unearthed by some future species archeologists and they'll piece together human language from it. But it won't be quite right because the messages aren't equivalent. I's not a Rosetta stone exactly.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's absolutely not, but it's possible that the Rosetta stone was never exactly the Rosetta stone, because as translation theorists would say, the idea of complete correspondence between two language, is a bit of a myth. There's always a slippage. There's always something that doesn't work quite the same way. Which is one of the wonderful things about language.

HZ: Do you think that Ferrero put as much thought into this as you have?

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: No. But that's fighting talk. And I would like to issue a disclaimer, saying of course they put a lot of effort into it.

HZ: it. Well, maybe this is the way to lure them out to come and talk to you.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: No, of course they put a lot of effort into it. They must have spent huge amounts of time corralling translations from different parts of the world. The graphic design on it is incredibly difficult because you've got a tiny, different, tiny space to do that. There's presumably all sorts of negotiations that go on with Ferrero national branches. There are constantly changing req regulations. There are addresses on there that have to be changed. There are production dates. They have to be changed. So yes, obviously there are people who have spent a lot of time doing this and probably only this. However, in terms of actually thinking through the implications of what they're doing, I would like to think that I've thought about it a little more expansively than they have. Because ultimately - and this is not a criticism - they're doing this for a very, very specific reason. They're not doing it out of a love of language, or a fascination with the world. They're doing it because they need to do it. So in that respect, I think I probably have spent more time on it than they have.

HZ: Yeah. I think their priorities are probably toy, chocolate. Those are the things they care about, they wouldn't necessarily have as much affection as you do for this document and what it means.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: It's not good for them for their product to be dangerous. Simultaneously, they genuinely don't want to kill small children and legally they have to protect themselves if that were ever to happen. So it's a kind of virtuous mixture of compulsion and choice.

HZ: Speaking of the toys, I haven't even looked at mine, because it's all about the message; but let's see what I've got. I've got two little brown pieces and a white skeleton thing. And I probably should look at the instructions.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: There is. It tells you how to put them together. There's also a QR code on a lot of them.

HZ: Let's not go that far. This really shouldn't be that challenging, and yet…

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Somehow it is. I think the toys on their own are not that exciting, but I can imagine that if you have a collection with 500 of them, it would probably would look quite interesting. What is it?

HZ: It's a walrus with some kind of wings.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Why?

HZ: I'm never going to know, because they don't tell you.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: They don’t explain.

HZ: And there's a little target with a fish on it. Oh! You’re supposed to hurl it at the target. So it's like a little walrus weapon.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: Lovely.

HZ: Isn't it. Lucky me.

HZ: It's a pretty nice walrus with wings; but, thanks to Keith, it's not the true prize in the Kinder Egg now. The chocolate, a momentary pleasure. The toy, minutes of entertainment. The warning? Well there’s this episode, that’s a lot of minutes; and then there’s Keith’s whole book.

KEITH KAHN-HARRIS: The point is, is that these tiny little ephemeral details with everyday. life, you know, then most people don't keep track of them. And even collectors tend to be interested in the more exciting bit. So there are people who collect warning messages, believe it or not, but most kids are surprised collectors collect the toys as you'd imagine. And it makes me think about what are those tiny details that are eloquent about the way the world works, that we just ignore all around us. And so sometimes it's useful seriously to actually look very, very closely at something that seems entirely peripheral to one's own daily life.

HZ: You heard from Keith Kahn-Harris, sociologist and author of books including The Babel Message, all about the warning message in the Kinder Surprise Eggs, and in it you’ll learn a lot more about his studies of the message and his efforts to get it translated into far more languages, and he’s still collecting translations, maybe you could supply one? I’ll link to his list of wants at theallusionist.org/kinderegg.

The Allusionist is an independent podcast supported by you listeners with your attention and in some cases your patronage. Patrons get fortnightly livestreams with me and my dictionaries, and a 24/7 Discord community, this week Rilla has been giving advice about making your own vinegar from apples. It’s a nice place to be. Join us at patreon.com/allusionist.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

exciton, noun, physics: a mobile concentration of energy in a crystal formed by an excited electron and an associated hole.

Should have had a content warning on that maybe. Try using ‘exciton’ in an email today.

This episode was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman. The music is by Martin Austwick of palebirdmusic.com, and what you’re hearing now is, I gave him three Kinder Eggs and said, “Oy Martin, make a music with those.” And he did.

Our ad partner is Multitude. To sponsor an episode of the Allusionist, contact them at multitude.productions/ads.

Stay in touch with me @allusionistshow onTwitter, Facebook and Instagram. And to hear or read every episode, see the full dictionary entries for all the randomly selected words, browse a lexicon of all the words ever covered in the show so you can find the relevant episode about it, and get more information about the topics within each episode, visit the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.