Visit theallusionist.org/hedgerider to listen to this episode and find out more about the topics therein

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, splat the linguistic rat.

Today: etymologies you requested! You sent in lots, thank you very much; this is just some, if yours is not included, comfort yourself with these reasons:

1. I’ve covered it before, browse through theallusionist.org/lexicon to find the relevant episode;

2. Some of the questions were big enough to require their own episode so sit tight because I hope to be able to bring you such soon;

3. Your questions were good, but either the dictionary or my brain couldn’t supply a good answer; that’s just how it goes sometimes.

I must admit, I spent a bit too much of yesterday evening trying to figure out, per a request from Cait, whether the word ‘seminal’ is sexist. What’s my verdict? Listen on to find out!

On with the show.

To start, just a little bit of etymology I couldn’t squeeze into the last episode about zero: ‘nought’, which conveys both nothingness and the number. It’s from Middle English, and it meant ‘zero’ before English had zero; but it was a respelling of Old English ‘nowiht’, meaning nothing.

If you say ‘aught’ to mean zero, which I believe is the American English option: that got all flipped around, because aught is from Old English ‘awiht’ which means... everything! How did everything come to mean nothing? It’s all thanks to that old agent of chaos, misdivision! Not content with making a napron an apron and a numpire an umpire, it turned a nought into an aught.

Nought also had another meaning, which is retained a bit in ‘naughty’: nought meant something evil. From there, let’s get stuck into your requests that feel relevant to the halloween season. Which is apparently what the month of October is called now. Look, I didn’t invent it, just reporting it.

Brad says: “Conjure - how did it go from 'swearing an oath together' to 'make appear from up your sleeve'?”

Great question Brad! Although I think it has only had the rabbit in hat kind of meaning for a couple of hundred years. Stage magic had been around for a long time before, but tended to be called other things, like ‘legerdemain’, French meaning light of hand.

‘Conjure’ has been around in English since the mid-13th century at least, and did mean ‘to summon with magic’, same as the Old French word it came from, conjurer, which came from a Latin verb coniurare, which, as Brad said, means to swear an oath together, the con- is together and the -iu- part is from Latin word ‘ius’ meaning law, that’s same root as jury, judge, justice.

Coniurare also meant to pray, because swearing an oath was to a deity, so the concepts are not that far apart. But, somewhere along the way, conjure got a little whiff of swearing an oath with a demon. Hey, guess what else has swearing-an-oathy etymology: exorcism! A word that appeared almost synonymously with conjuring a few hundred years ago when the words were both newish to English. They’re both summoning spirits, the crucial difference between them being that exorcisms were considered legit because priests did them, to summon and thus banish of spirits - and also to study the spirits because gotta know your enemy, right? Whereas conjuring, not academic summoning of demons, just for nefariousness. But what if you were summoning spirits for non-demonic purposes? Nope, naughty!

Remember there was a long period in the English-using nations where Christian rituals, incantations and props good, all others bad! Monotheism good, panetheism bad!

Although for much of human existence, magic and religion have bubbled away together in the same cauldron - cauldron is from the Latin ‘hot bath’, by the way - as Christianity took hold across Europe, non-Christian practices had to be sequestered off as paganism and paganism had to be demonised literally and figuratively, to keep people Christian.

I’m not sure I’m really able to answer your question, Brad, about exactly when and why conjure underwent this transformation from oath-swearing to spirit-summoning and then to performing illusions, but maybe one way to stop people wanting to conjure spirits was to effectively defang the word by associating it with pulling a plastic bunch of flowers out of your sleeve.

Relatedly, ‘supernatural’ used to mean ‘divine’, because who’s above nature? God, of course! Always lording it over everything.

This request comes from Porter K Ludwig: “Warlock / Witch / Wizard / Sorcerer; basically any of the terms related to magical dudes. A lot of media tends towards a witch is a female wizard, but that feels weird and reductive, I think?”

Well, compared to wizards, witches do take the lead...at being executed for witchcraft! Although not exclusively, and not in Iceland; I recently went to the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft where there’s a list of the 21 people who had been executed for witchcraft in Iceland, and twenty of them are men. But, while a lot of the witch executions in countries such as Britain were because of misogyny, what I gleaned at the museum is that in the Iceland of yore, women weren’t getting executed because they didn’t think that women were up to the task of witchcraft. You’re either executed for being a witch or not good enough to be a witch, can’t win! Or, were Icelandic women just way better at getting away with it?

My favourite of the unfortunate men was Sigurður Jónsson, who, I quote, “admitted among other things that he had fought a ghost and frightened it off with the help of herbs and his own semen.”

“Er, look, officer, there’s a perfectly innocent explanation for this, I was just cooking dinner and self-pleasuring when a ghost happened to appear and I did my best with what I had to hand...”

Sometimes it would be useful if a podcast had footnotes, wouldn’t it, so that if you came here just for etymology, you didn’t get derailed by a tale of someone frightening off a ghost with semen.

Is. Seminal. Sexist?

We’ll get onto witches in a moment; let’s get the magic lads out the way first.

I covered ‘warlock’ in episode 28 WLTM part 1:

“'Warlock' started out as the Old English ‘wærloga’, which meant a traitor or a liar. ‘wær’ meant ‘fidelity’ or ‘vow’, and the ‘loga’ was a lie. So wedlock was making a pledge, and warlock was breaking a pledge. 'Warlock' also used to refer to the Devil, and by extension, it came to mean people who associated with the Devil, and thus by the 1500s it was applied to sorcerers, thus it is now considered by some pagans to be an offensive term. And fair enough - just because you’re a gentleman witch doesn’t mean you’re evil. #NotAllWarlocks.”

‘Sorcerer’ started out ‘sorcer’, got an extra -er cos that’s magic - nah it’s back formation from ‘sorcery’ which was a couple of hundred years older, been around since about 1300, and ultimately that came from a Latin word for fortune-telling, so I don’t think there’s been such a journey for the word sorcerer.

Whereas ‘wizard’ arrived in English around 600 years ago, and it was a combination of ‘wise’ and ‘-ard’, wise meaning wise, because wizards then were sages, and -ard which is the same suffix as buzzard, drunkard, coward, bastard - it was kind of an insulting suffix, actually.

It’s not the same -ard as in ‘haggard’ though, that was from the Old French ‘falcoun haggard’ meaning falcon of the woods; haggard meant unruly, like a hawk. ‘Buzzard’ was also from Old French, ‘buisart’, an inferior hawk. Rude!

But we’re not here to redeem buzzards, we’re here for wizards! The word became magical in the mid-16th century, because wisdom IS magic, or rather for much of human history, philosophy, religion, magic, science, occult didn’t have so much distance between them. If you go far enough back, maybe 2,500 years ago, to the Greek origin of the word ‘magic’, μάγος, it meant a learned person or priest, often the same thing, but, μάγοι was the word Greeks used to refer to Persian priests, and it wasn’t intended to be respectful, it was meant to imply that the μάγοι beliefs were outside of the realm of what was acceptable in Greece. But then when the Roman Empire got hold of the word, they were using it against Greek and Roman peasants, whatever they were worshipping was not appropriate, and just to amp that up, not only was it not appropriate, it was highly deviant and deceitful and evil. So there’s that theme again: magic was separated off from certain religious structures, then marginalised and vilified as much as they could manage. The etymologies show how these concepts are rooted together then sprouted off into different directions.

You’ll notice that these ancient Greek and Latin words tended to refer to men, and I don’t think it’s coincidental that for a lot of time in a lot of societies, women didn’t get much of a chance to flex religious or spiritual powers, or get the credit for having the capacity for such. Not capable of scaring off a ghost with semen!

So let’s look at the word ‘witch’. It is from the Old English wicce, spelled W I C C E, and the masculine form was wicca with an A - yes, like the modern religion wicca, which was named that mid-20th century. Wicca in the Old English times meant a wizard - the ‘wic’ also appears later in the adjective ‘wicked’.

‘Craft’ in the word ‘witchcraft’ at the time meant a strength as well as a skill, so witchcraft was powerful while it also involved practical abilities like herbalism. Along with the word witchcraft/wiccecræft, Old English had the word drycræft, a dry was a priest or magician, from the same word and principle as ‘druid’. After the French had taken control of England, drycræft was supplanted by ‘magique’ - but ‘witchcraft’ remained, presumably to keep a specific bias against whatever the lady witches were up to.

There were quite a few old English words for witches meaning slightly different things, like the witches had compartmentalised skills then, not like the all-rounder witches later. There was gealdricge, a woman who casts spells and incants; scinnlæce, a shapeshifter or one who communes with phantoms; and lybbestre and lyblæca - the ‘lyb’ was from the word for ‘leaf’ so they were making potions - or just making tea, not all leaf-water is a threat to society, cmon!

‘Crone’ however is a witchy word nowadays, but only has been that for the last few decades; for the several hundred years prior to that, it was just an insult for an old woman, it was from a French slang word ‘charogne’ meaning ‘old sheep’, but literally a dead body, the same origins as the word carrion.

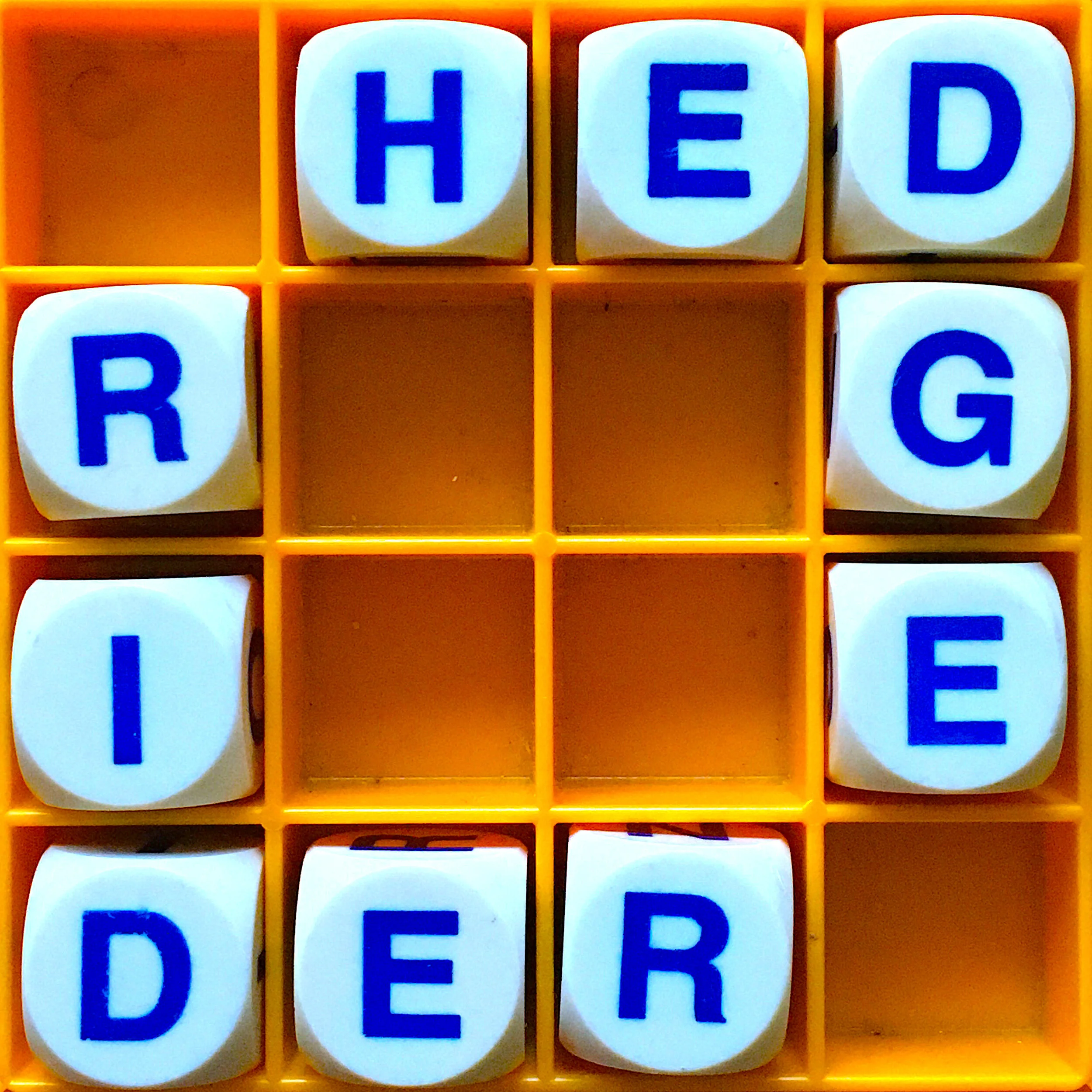

Meredith wants to know about the hedge in “hedge witch”.

There are some explanations floating about: because hedge witches we solitary witches working a lot with herbs. They lived outside the village, beyond the hedge, and/or they gathered ingredients from hedges and woods. But I think a factor to consider is that whereas nowadays we’d understand a hedge to be made of living shrubs or trees, in Old English, a hedge meant a barrier of any kind or a fence. So I think the term is likely less to do with where the hedge witches obtain ingredients and more to do with their separation from other people, although the modern city-living hedge witch may have changed the paradigm.

There are some Old English and Old Norse words for sorceress or witch that translate to ‘hedge rider’; the Old English word was hægtesse, we’ve got the word hag from it as a souvenir. Thanks! You shouldn’t have! But the hedge-rider words referred to witches and ghosts - and I think they’re playing with that image that these beings were existing in two worlds, the so-called civilised one and the wild, supernatural one beyond the hedge. So perhaps the hedge in ‘hedge witch’ is just the metaphorical hedges we met along the way.

Lola: “And what about ‘excelsior’? How did wood shavings get such a fancy name?”

I never knew about the wood shavings! You people teach me so much. OK, this is not technically a magic one, but excelsior sounds quite magical. It’s an exciting name for a substance that is more boringly called ‘wood wool’ or ‘wood flour’. It has many uses, such as upholstery, erosion control mats, archery backstops, fake straw in gift baskets. My family has a teddy bear that belonged to my grandfather, iis more than 100 years old and is still holding up - stuffed with excelsior! It also used to be used as absorbent material in late 19th century nappies, wound dressings, and early disposable menstrual products.

But why does this substance have such a grandstanding name, from Latin meaning higher? Unfortunately, it is as clear as wood wool. The word was around before it was a wood wool word, but in that form it first appears in patent applications in the 1860s for mattresses stuffed with a substance with the commercial name ‘excelsior’, some enterprising wood-mincer decided to give it that name as their brand - perhaps inspired by it being the motto of New York state since 1778? Or just marketing: boring substance, exciting name, reach for the stars, stuff your mattress, absorb your blood, stop the jars of chutney crashing into each other in a gift hamper, excelsior!

On to the non-witchy part of the programming:

Sarah: Gaffe.

That’s all Sarah says, “gaffe”, so I take that to mean what is the origin of ‘gaffe’ like when a public figure makes a big blunder, rather than gaff without an E that in Britain means your home, but further back, 18th 19th century, was slang for was slang for a music hall or theatre or funfair, which might have come from the Romany word ‘gav’ meaning a town.

The other kind of gaffe, the foot in mouth gaffe: that is from a 600-year-old French word meaning a fish hook. A fish hook?? My research was alas coy about why a fish hook would come to mean saying some facepalm-inducing thing - it’s as welcome as a fish hook to the mouth? It causes one to recoil as if the mouth had been caught by a fish hook? These gaffes also sometimes meant objects like a spur when riding a horse, so perhaps a gaffe is something that hurts. Or, maybe it’s from English and Scots words ‘gaff’ meaning loud talk, and etymologists just got confused, reeled in by a passing fish hook.

Tony: “The names Javier and Harvey. They sound very similar, but is this just a coincidence?”

Yes. Zaltzman’s second law of etymology: don’t get too comfortable if something sounds like another thing, or spelled like another thing.

Harvey is an Old French name, so at least 1000 years old meaning ‘battle worthy’; Javier is from the 16th century Roman Catholic missionary Francis Xavier, spelled with a Basque X rather than the Spanish J - he’s patron saint of a lot of places around the world from Mumbai to Indianapolis, but also of plagues, so pop him a prayer if you’re so inclined. His name refers to the town in Northen Spain where he was born, Javier/Xavier; and that derives from the Basque term ‘exte berri’ meaning ‘new home’. There are equivalents in other languages, Casanova in Italian or just Newhouse in English.

Jerry: “Clove. How can it be a spice and a section of a head of garlic?”

Let this comfort you, Jerry: it’s really two different words. Zaltzman’s second law again. The one that is the spice is from Latin ‘clavus’ meaning nail, because the cloves looked like nails - metal nails, not fingernails. The garlic one is from Old English ‘clufu’ which derived from a word meaning something that cleaved or clove apart like the pieces of a head of garlic, the ole spear leek.

Rosalie: “Nice. It often seems so loaded when people call you nice. I do try to be nice, but I say I’m being kind. Because nice is like I’m putting out my own doormat for you to downtrod me under. What’s going on? What’re wrong with nice? When did that all start?”

Well Rosalie, nice started out as not nice! It meant ignorant or clumsy! (And I just learned that ‘clumsy’ meant to be benumbed by cold, when it started out 400ish years ago. Which figures, as we learned about with getting toasty!) English got ‘nice’ from a Latin word ‘nescius’ which meant ‘not knowing’, ne- the negative prefix and the verb scire to know, same one that begat ‘science’. There’s still an English word ‘nescience’, which means ignorance or lack of knowledge.

So that’s where ‘nice’ began, in the 1300s, and then it went on the move; in the 1400s, it started to mean fussy or fastidious; I’m not sure why, maybe that was an indicator of silliness to be fussing over something? From there, it came to mean dainty, delicate, scrupulous, well dressed - what a turnaround! Nice became a complimentary adjective, and this is why we can believe in redemption, people, if it can happen to nice maybe any of us can turn ourselves around, go from ignorant to pleasant, kind, thoughtful.

So where, how did it go wrong for nice again? It was a victim of its own success. It was used for people so pleasant, so refined, so unvulgar, that ‘nice’ became a bit insipid. Two hundred years ago, Jane Austen’s characters were mocking people who overused the word. In 1946, “Nice guys finish last” was supposedly coined by Leo Durocher, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who said something like it about their rival baseball team the New York Giants, who were losing, but “nice guys” was the polite way to refer to the enemies publicly. So he wasn’t saying that they were losing because they were nice, but that is what the phrase soon came to mean, as it was propelled through the gender relations of the 1950s and beyond. Nice guys, not macho enough; nice guys not compelling to womenl then also a strain of nice guys who are nice to get what they want, which is too manipulative to be nice but try telling them that, they will pop off. Meanwhile nice girls = prudes. Nice time = unexceptional.

That’s where I think it all went wrong for nice, Rosalie. But I think nice can be redeemed again. It’s hard to shake a reputation for blandness, but there’s got to be room for things that are pleasant and so easy to digest that they don’t inspire more exciting adjectives. Right? Give nice another chance! And then it’ll turn bad again - that’s the cycle, and remember we can’t have nice things.

“Is seminal sexist?” Cait asked.

‘Seminal’ and ‘semen’ are both from the Latin word for ‘seed’. As is the word ‘seminary’, which originally meant a plant nursery.

So you could argue that etymologically it’s a Latin word that went up several separate paths, and ‘semen’ and ‘seminal’ have nothing more to do with each other than that; but then, would the word ‘seminal’ mean something so important if some people weren’t so proud of their bodily emissions and the same demographic called dibs on the lexicon… Is seminal sexist? I’m sorry to hedge a bit, and I don’t want to play into the hands of people who are always complaining, “You’re not allowed to say anything any more! Political correctness gone mad!” So instead I’ll say: you don’t have to use this word. Something like landmark or foundational would work instead, no bodily fluids there.

The Allusionist is an independent podcast, made by me and by you, because you supplied your questions and and eartime and Patreon patronage. I was recently on the show Podcast Playlist from the CBC, recommending a few other podcasts I like, so check that out if you’re in the mood for more speech-based audio in your life. And sign up to patreonise this show at patreon.com/allusionist for extra behind the scenes info about the show, additional things I learned in Iceland as well as the ghost semen thing, and bonus word facts. Oh! ‘Fact’ used to mean ‘evil deed’ about 500 years ago! That’s a thematically relevant bonus etymology for you all. And another: ‘grimoire’, as in the spellbook, comes from the same word as grammar! As does glamour, which meant an enchantment! This etymology train never pulls into the depot.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

popple, chiefly archaic, verb: (of water) flow in a tumbling or rippling way. Noun: a rolling or rippling of water.

Try using ‘popple’ in an email today.

This episode was written and produced by me with questions from you, thank you very much, and music by Martin Austwick of palebirdmusic.com. Find @allusionistshow on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. And to hear or read every episode, find more information about the topics therein, see the full dictionary entries for the randomly selected words, browse the lexicon of all the words ever covered in the podcast, visit the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.