Listen to this episode and find out more about the topics therein at theallusionist.org/tiffany

This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, spot a very glamorously-dressed language eating a breakfast pastry outside a well-known jewellery store.

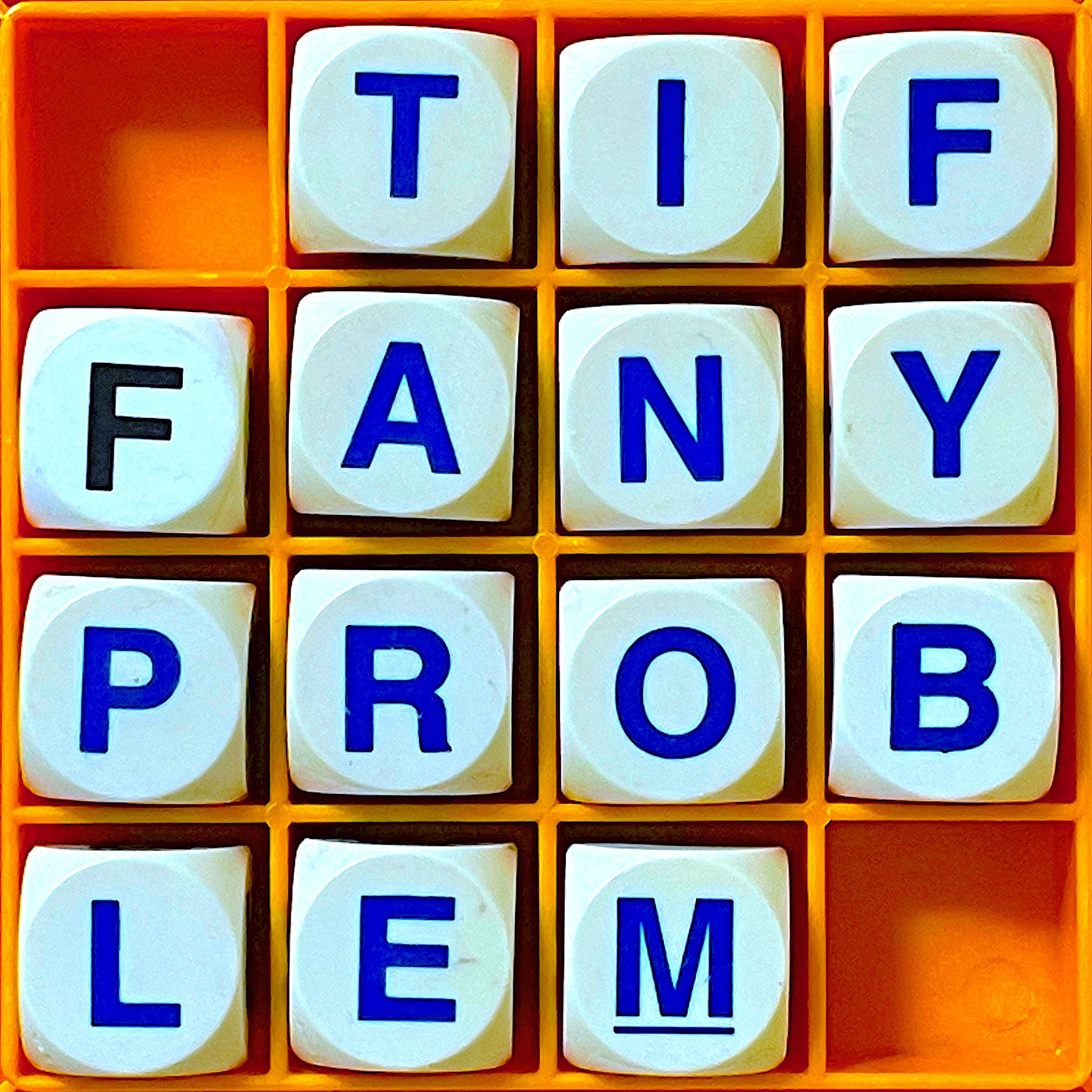

Today’s episode is about anachronism, but really anachronisms that are not anachronisms - so… anachronISN’T?

Yay, glad to have curdled your linguistic milk straight out of the fridge!

Just a reminder: there are transcripts for each episode, including this one, at theallusionist.org/transcripts. Also on the website, links about every episode’s topic, and event listings - people in Australia, keep an eye on those because I am coming your way in July.

On with the show.

HZ: This episode is about a phenomenon called The Tiffany Problem. And I just want to emphasise to any and all listeners called Tiffany: you’re not the problem. It’s not your fault. It’s not you, it’s everyone else.

SONG after the 1995 hit song ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ by Deep Blue Something:

And I said what is the problem with Tiffany?

They said it’s if you call a character that

In a historical novel or period piece

Because people won’t believe that that name is old.

The phrase “The Tiffany Problem” was coined by the science fiction and fantasy author Jo Walton, here she is:

JO WALTON: I wanted to talk about this problem that is the Tiffany Problem. Tiffany is a name that, to us, sounds modern. It sounds like a modern name, it does not sound like an old-fashioned name. It doesn't ring as authentically old, even though it is 12th century and attested in English and French documents back to the 12th century.

HZ: It’s true, Tiffany was quite a common name in medieval English and French. It means “the appearance of God” and was often given to babies born on 6 January, the Christian festival Epiphany, because Tiffany was an Anglicisation and Gallicisation of another name for Epiphany, Theophania.

JO WALTON: Which does sound authentically old, right? Theophania sounds like an old name, but Tiffany totally doesn't. It doesn't sound like a name that you could give a character in a historical novel.

SONG after the 1987 hit ‘I Think We’re Alone Now’ by Tiffany:

Whoa Tiffany, you’re such a modern girl,

Singing and dancing around the shopping mall!

JO WALTON: What we the readers know about the name Tiffany is incorrect. Nevertheless, as a writer, you cannot use the name Tiffany.

HZ: What made you choose the name Tiffany specifically for the Tiffany Problem? Because there are other names that people tend to think are modern that are actually old, like Samantha and Gary and Chad.

JO WALTON: I just came across this Tiffany/Theophania thing a long time ago, something that I was reading ages ago, like decades ago. So it was sort of in my mind. And when I started thinking about this as a problem, it just sort of came to mind in an encapsulated it. It might be that Gary was the name of kids that I was in school with whereas Tiffany wasn't, it seemed more modern than that. And sort of American. It did not seem like even a name of my childhood when I run across it. So it was anomolous, in that way. Anyway, I think it's a good name for it. I think it's nice to have something called after women.

HZ: When you're creating a fictional world and you want to include something that you know is historically accurate, but you don't want to get bogged down in having to explain to the listener that actually, yes, this is historically accurate, they can believe it: how do you handle that?

JO WALTON: Sometimes I know that it's going to be a problem that people won't know about it because I didn't know about it before I started zooming in on that period. And this is a wide problem with writing historical fiction, or things set in history - because for me it's usually fantasy in some way - writing things informed by real history or that were set in real history or something that feels like real history. It's not just names; it's all kinds of things.

HZ: In days of yore, Vikings wore brightly coloured stripy trousers; T-rexes didn’t walk upright; Greek and Roman statues were vividly coloured; in days of yore, no, everyone was not heterosexual, cisgender or white; in days of yore, people ate ice cream, and used singular they, and said “like” in the ways that annoy people today; in days of yore there were batteries; multistorey apartment buildings; air conditioning and central heating; syringes; spectacles; vending machines.

JO WALTON: You can have a character called Tiffany, but you've really got to put a lot of effort into it because the reader will be pulled out of the story by Tiffany.

HZ: Where a concept or character might come across as anachronistic even if it isn’t, Jo will be very careful how she sets it up. Or she’ll get the characters she’s writing to do it, put the problem into their mouths.

JO WALTON: You can have characters have a conversation about an aspect of something that's broken. And in doing that, they will learn about the thing that's broken, so that they'll accept it. That's one simple technique for dealing with that. Or I won't use it. Sometimes I will decide damn, I would love to have this character called Tiffany, but I can't. And I'll call her Helena or something else because I just can't do it for a modern reader.

HZ: But that perpetuates the Tiffany Problem, because Tiffanys don’t get represented in these historical contexts, so they stay modern in people’s minds.

JO WALTON: I've mostly been able to get away with it by setting it up and doing it, but you've gotta be aware that there is this Tiffany barrier there in people's minds where you've got to break it down slowly, because people just won't believe it.

HZ: So many things to consider, when you’re naming characters in fiction.

JO WALTON: Does this sound authentic? How does this, what does it seem like class-wise? What abbreviations of these names would people the age of younger brothers and sisters use? Because you really have to get that stuff right. Well, you don't have to, you can just screw it up; but it’s better if you get it right.

HZ: If you’re writing modern children, are you giving them contemporary kids’ names or use the names that were common kid names in your own childhood? More likely the latter, Jo Walton reckons.

JO WALTON: People writing books with kids in are inclined to give the kids names that kids had when they were that age.

HZ: Which might be anachronistic, given how naming trends of the author’s childhood may not be those of the era when their book is set. For additional confusion, consider how in the first couple of decades of the 21st century, there has been a trend to revive older-sounding names, names that were popular 100 years before, Archie and Beatrix and Olive and Mabel, names that in a novel you would accept for a character born in the 1900s but maybe not for one born in the 1980s. But for a novel set, say, in the 2040s, will that resonate for a reader in our current era, the early 2020s?

JO WALTON: Particularly when I'm writing things set in the future - I've got one story where the grandmother is called Britney, and the people of the parents' generation are called Walter and Maud. Because that's the kind of thing that's going to happen.

HZ: And maybe, hundreds of years from now, archaeologists dig up a small pale blue Tiffany box, and after some time studying the other documentation they have unearthed, historians deduce that the box came from a place that sells breakfast.

Tiffany IS an old name, as aforementioned, but after its period of medieval popularity, it wasn’t all that common as a first name until the latter part of the 20th century. It was around as a last name all that time though, and variants like Tiffin and Tiphaine. The actor Richard Tiffany Gere, also known as Richard Gere, has that middle name from his mother’s last name. As a last name, Tiffany became famous as the jewellery business, named after its founder Charles Lewis Tiffany, who opened up shop in 1837 selling stationery and ‘fancy goods’.

If you want to credit Tiffany fancy goods for the revival of Tiffany as a first name, I think you have a case - that business is the titular Tiffany in the novella and film Breakfast at Tiffany’s; the film was released in 1961 and Tiffany enters the top 1000 American female baby names in 1962, although it’s a slow rise, it doesn’t enter the top 100 till 1970 and not the top 20 till 1980, where it remains for most of the decade, remains fairly popular through the 90s though by the end it slides gradually back down towards the hundreds again. In Australia, France and the UK, it also crested in popularity in the 1980s and 90s.

In 2021, Tiffany was the 864th most popular female name in the USA, with 315 new Tiffanys being registered. Name data does not exist for the 13th century so I can’t compare directly.

SONG in the style of 13th century chant:

Tiffany you’re such a modern girl,

Singing hymns and praying by the convent wall.

HZ: Any depiction of history has been editorialised with the standards of the time of that depiction.

JO WALTON: But it's things that fit with the prejudices - the more it fits the prejudices, the more people will believe it. People have this belief, this prejudice, that history was terrible. And in many ways it was terrible; but it's good things that they often have a hard time believing.

HZ: Do you think people have to believe, without actual evidence, that we're better humans than long-dead ones? That there's linear progress?

JO WALTON: It could be that. It could well be that. I think some people do want to believe that there is simplistic progress and that we are the best ever. And other people want to believe the opposite, that we're the worst ever. But either one of those answers fits with the way that people tell stories, it fits with people's prejudices and beliefs: we are the best; we are the worst. Whereas it's really complicated and fractal. And we're much better on some things and much worse on other things.

HZ: We’re not saying that fiction has to be real - and much of Jo’s work is not set in the real world but fantasy worlds - but the reader has to believe it and not be jolted out of it by details that seem jarring, for example how nearly all the cowboys in American film have been white but a large number in the 19th century were Mexican, Black and Native American. When the jolt comes from disparities between historical fact and common perceptions of the past, that shouldn’t be avoided.

JO WALTON: I sometimes talk about this as it's rolling the ball up hill. It's very easy to roll downhill, the ball wants to go down the hill and gather momentum, and there's always a way of telling the story that is rolling the ball downhill. But sometimes, when you're talking about history and the complexities of history and human society, you're really rolling it uphill, and you've got to make extra efforts to get it uphill, and to get people to go along with you, than if you give a downhill story. I'm not very interested in downhill stories, even when they're not lies, because they're kind of boring. But the uphill stories take more work. And whether that's the true stories of history, or the fictional stories that I'm writing novels about, it's always kind of a bit uphill.

SONG after the 1987 hit ‘I Think We’re Alone Now’ by Tiffany:

Whoa Tiffany, you’re older than you look,

But I can’t call a grandma ‘Tiffany’ if I write a book, no no no.

HZ: Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer and you can find her novels, poetry, plays, essays, recipes and dates of upcoming appearances at jowaltonbooks.com.

The Allusionist is an independent podcast kept going by the generous Patrons at patreon.com/allusionist who in return for their largesse receive behind the scenes intel about the show, regular livestreams and their own Discord community, wherein the other day I asked people if they could think of examples of the Tiffany Effect and Eric cited ‘unfriend’ - turns out that word has been around long before social media, as a verb in 1600s, as a noun from the 1200s, meaning an enemy. No enemies in the Allusioverse, just friends, join us at patreon.com/allusionist.

Your randomly selected word from the dictionary today is:

fleer, verb, poetic/literary: laugh impudently or jeeringly. Noun, archaic: an impudent or jeering look or speech.

Try using ‘fleer’ in an email today.

This episode was written and produced by me, Helen Zaltzman; thanks to Erin Wade. the original music was composed, played and sung by Martin Austwick of palebirdmusic.com and the podcasts Song By Song and Neutrino Watch.

Our ad partner is Multitude. To sponsor an episode of the Allusionist, contact them at multitude.productions/ads.

Stay in touch with me @allusionistshow on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, and to hear or read every episode, get more information about the topics and guests therein, see the full dictionary entries for all the randomly selected words, browse a lexicon of all the words ever covered in the show so you can find the relevant episode about it, and for event listings for upcoming live performances, visit the show’s forever home theallusionist.org.