Visit theallusionist.org/tokipona to read about and listen to this episode.

HZ: This is the Allusionist, in which I, Helen Zaltzman, open up language to see a tiny plastic ballerina turning around and around.

On with the show.

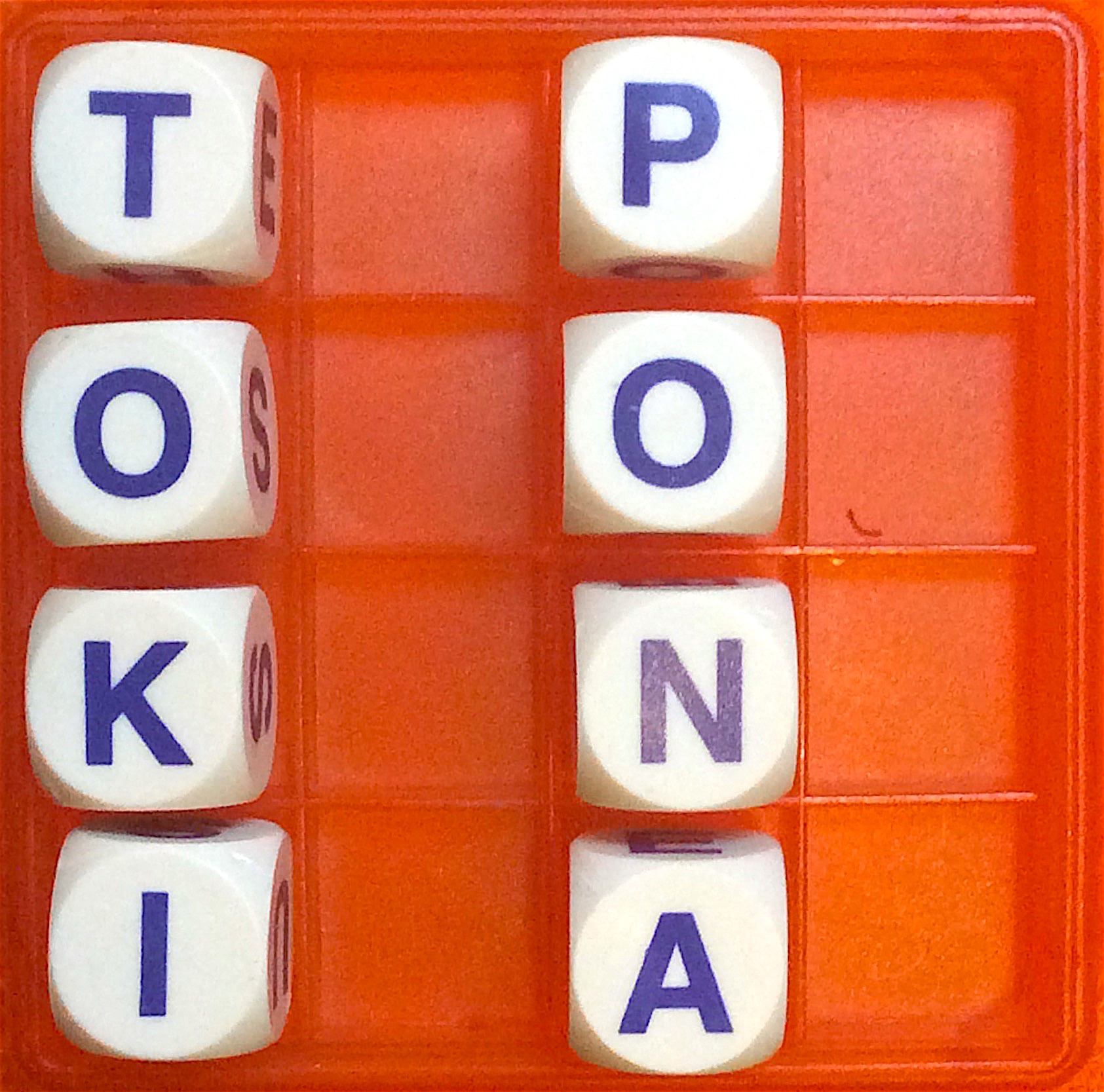

HZ: There’s a language which is said to be the smallest language in the world. It has around 123 words, five vowels, nine consonants, and apparently you can become fluent in it with around 30 hours’ study. It’s called Toki Pona.

SONJA LANG: The word ‘toki pona’ means literally ‘good language’, or ‘simple language’. ’Toki’ means talk or language or speech or communication; and ‘pona’ means good or simple or friendly; so it’s all those ideas in one.

HZ: So it’s a very positive language.

SL: Positive, simple language. Exactly.

HZ: Sonja Lang invented Toki Pona in 2001. She’s a linguist who grew up in Canada speaking French, English and the French-Canadian dialect Chiac; then studied, variously, Spanish, Latin, German, Finnish, Cantonese, American Sign Language, Esperanto, Dutch...

SL: I didn’t intend to make a language, but somehow spontaneously, after learning many different languages, my brain was trying to restructure itself and understand all these different things I was learning, and it just came up with this way of organising words and ideas. So I had to write it down and let it out somehow, and I did, and it became Toki Pona. But there were some conscious design decisions as well. I wanted to keep things simple.

HZ: Constructed languages go back a long time. There was quite a movement in the 17th century to find a universal language, although so far none has quite achieved world domination - Esperanto is the most successful, with an estimated 2m speakers.

And constructed languages have myriad different intentions. Blissymbols was designed to be a universal writing system, and is now used to teach people with severe speech or learning difficulties to communicate. There are computer programming languages, which are not exactly optimised for chitchat. There are languages invented for books and TV and film, like Elvish and Na’vi and Klingon.

Some constructed languages are experimental, like Kēlen, which has no verbs and deliberately sounds non-human; and there are Lojban and Ithkuil, which aim to allow users to express any thought precisely.

But Toki Pona is different. It doesn’t aim to replace other languages. It doesn’t even really share the primary intention of most languages, to help humans to communicate easily with other humans. It is somewhat more introspective. Sonja calls Toki Pona her ‘philosophical attempt to understand the meaning of life in 120 words.’

SL: It’s all about minimalism. If I can express something with fewer words, obviously that’s better. And part of that was also a mental thing - a cognitive, psychological thing: how can I reduce my thoughts, instead of thinking about 20 million different things? Someone’s surfing the internet and they have twenty different tabs open - no, let’s just have one tab. Simplify your workspace; simplify your thoughts, was a core part of the endeavour. Like, a way to audit your thoughts and look at what are you thinking about, what are you worried about, and simplify the problem.

HZ: I do always have dozens of tabs open on my browser, and my thoughts have largely gone unaudited ever since I became conscious of having any, so I was intrigued by Toki Pona. Especially as one of my fellow Radiotopians decided he wanted to learn it with me.

NATE DIMEO: This is the Memory Pallusionist. I’m Nate DiMeo.

HZ: As well as helming the heart-rending history podcast The Memory Palace, Nate is fond of learning new languages.

NDM: Basically I’ve learnt the rudiments and to be polite in nine languages just for fun. The very first thing you learn is, “Excuse me ma’am, do you speak English?”

HZ: And if she says “Yes,” you don’t need the rest.

NDM: Exactly, then you’re done. That’s the short course.

NDM: The notion, when I read about Toki Pona, not only was it a fun language that I could hopefully learn in the course of a week, also its goal seems to be poetic, and I’m a sucker for that kind of thing.

HZ: Before starting to study Toki Pona, I wanted to get a grounding in how the language itself had started - from the very rudiments, such as how its words were built.

SL: I did intentionally seek out phonemes, sounds that are common in most world languages. Most languages have ‘a’ or ‘m’. These exist in almost every language in the world, so I took those first to be in the language. Then I looked a little broader and T and D, I merged those into one sound, because they’re very similar. So I guess my process was trying to simplify all the phonemes into a small set that anybody in the world could pronounce.

HZ: When it comes to grammar, are you trying to simplify what’s already there, or create a new and better system?

SL: The grammar came after. The first thing I tried doing was putting together nouns and noun phrases, so the idea of combining things in the language, e.g. the word for a friend is ‘yan pona’, good person. And the word for enough is ‘muti pona’, good quantity. I started combining these ideas together to form deeper ideas.

So once I had these little clusters of noun phrases, I had to combine them into a sentence. Eg the friend goes to the bank, and the bank is ‘money house’ because those are the two words that mean ‘bank’. So then I came up with little particles that divide between the subject and the verb and the object, to demarcate - i.e. what does this clump here do, ok it does this thing, ok to what? To that thing. That’s where the words like ‘li’ and ‘e’ come from.

HZ: In Toki Pona, the nouns can become adjectives, and verbs, and adverbs - the way they're ordered and the particles like ‘li’ and ‘e’ provide context for their function within the phrase. This is similar to how English syntax and prepositions work, but because in Toki Pona the words don’t change form according to which part of speech they are, it was a bit of a job for me to wrap my head around how it works. I imagined the noun/verb/adjective word as a cuboid building block, and the particle as, say, the triangular block that you put on top to make a house; or cylindrical blocks that turn the cuboid into a car. But sometimes paring things down this much can become complicated.

SL: There’s a very simple numbers system where you have words for one, two and many. You can say I have many books, I have one sister, I have two parents.

HZ: What if you have eight sisters?

SL: You can say ‘many’. There’s also an alternative advanced numbering system where you can say, hand has five fingers, so I have 'hand sisters and two and one', so you can add up. But for me the idea was to simplify, so let’s just say ‘many’.

HZ: It reminded me a bit of Roman numerals, having to add them together.

SL: Yeah, that’s the same idea.

HZ: There are also only five words for colours. ‘Walo’ is white or pale; ‘pimeja’ is black or dark, ‘laso’ is blue or green, ‘loje’ is red, ‘jelo’ is yellow. Combine those words to form other colours - similar to how the Old English for ‘orange’ was ‘yellow-red’, as I learnt in the brunch episode of this show. But maybe it isn’t that important to be able to label a particular colour. Toki Pona is not prescriptive; it’s suggestive, but because it’s not that specific, if I mentioned ‘soweli pimeja’, a dark animal, you might assume that I meant a grizzly bear when I was really talking about a dachshund. So Toki Pona demands that you make more effort to interpret what the other person might mean when you’re in conversation.

NDM: When I think about the value of a language as simple as this, I can picture us being truly fluent and having a very interesting conversation and it giving me a window into the way you think and me having more empathy for you as a result, and vice versa, and everything’s lovely.

HZ: In conversation, the speed at which you could interpret what someone was trying to tell you would make it not really a conversation. So what would that make it? And then to construct your own response, using your own particular shades of interpretation of how this particular language works so metaphorically.

NDM: One thing I really like about it is because of the comprehensiveness of English, French, Romanian etc, there is a fiction that we are understanding each other. We are coming to a fictional construction of understanding: the stoner case would be I say blue and see a totally different hue to what you see, and isn’t that cool, man; but the other aspect is, it is real, no matter what we’re communicating about -

HZ: We’re all just alone!

NDM: We’re all alone... But the philosophical side of me kind of likes that you go into a Toki Pona conversation understanding that your understanding is probably your own. The beauty of it is, you’re coming to something where each of our mutual understandings will mingle, will create this third thing that floats out there; and that’s kind of lovely.

HZ: My worry is, there’s such a limitation of expression, it might actually limit thoughts.

NDM: Oh, interesting. So if you and I were to stand in a field and look at the many types of birds, and there was a particular type of starling that struck you, not only would you not be able to say, “Hey Nate, look at that starling,” and I’d go, “Hey, what does a starling look like?” not only could we not share that experience, you think that it might actually limit the way you were processing the experience of seeing the field and these birds?

HZ: Yes. Not only practical things - sometimes there are emotional things you don’t know to identify because you don’t have the vocabulary to formulate thoughts and speeches about them. On the other hand, maybe that’s my conservative English-speaker thought: English with its hundreds of thousands of words, Toki Pona with its 123.

NDM: But I totally get what you mean about Toki Pona limiting thoughts. I feel like a true mastery of English in an Allusionist sense and understanding words and their meanings and their origins - the existential need for that, if I can throw myself on the couch and self-analyse, is I just really want to connect. I really want people to understand what I mean and what I’m feeling, and not feel like I’m alone in the universe as a result.

So with Toki Pona, I do kind of wonder if you and I are going to walk through some fields, on the one hand, I feel that me, the Memory Palace guy, and you, The Allusionist woman, are going to want to have a very word-filled conversation to dissect our experience. But at the same time, I also totally realise that you and I may well be better off going out and smelling the grass and processing the experience in a less mediated way, and maybe Toki Pona would allow us to do that better.

HZ: There was only one way to find out.

[Montage of HZ and NDM learning Toki Pona]

HZ: Kama pona, Nate DiMeo.

Welcome, Nate DiMeo.

NDM: Toki, Helen!

Hello, Helen!

HZ: Sina wile telo suno?

Would you like some tea?

NDM: Mi wile telo suno. Mute olo suno telo suno.

I would love some coffee. I really like coffee.

HZ: Jo. Telo suno li pona.

Yes, tea is delicious.

HZ: I hadn’t realised, until trying to construct phrases in Toki Pona, how much negativity is something I use in construction. I was trying to think of a word for ‘without’, and I couldn’t find that. And the slight undercutting of things, to get the right degree of -

NDM: Without-ness?

HZ: Yeah. The right degree of emotion.

NDM: So many positives are constructed through negative language. I did see myself thinking, “I don’t know how I can go down this road without beginning with a dispositive.”

HZ: And I don’t think I’m a particularly negative person. Maybe I use sarcasm or irony more than I consciously realised.

NDM: As someone from the UK, and someone born in New England, sarcasm and irony are the lifeblood of communication. And you’re right, those things are difficult to achieve in Toki Pona.

SL: That’s true, you might have to deal with reality! You can’t just gloss over it and say something funny. But that’s a coping mechanism, isn’t it?

HZ: Yes!

SL: Humour is extremely important. But you’re right; I never thought of it with that angle, because Toki Pona is very blunt in a certain sense.

HZ: You’re right I use humour as a coping mechanism; it’s an easy way to grease the social wheels. I’ve never been able to speak another language idiomatically enough to be able to do that outside of English.

SL: It’s a good sign; if you can be funny in another language, you’re well on your way to mastery.

HZ: I’ll just be a nothing in other languages! Everything that I consider to be myself will be nullified in other languages.

HZ: What I have found is that I’m so used to having a very very broad palette with which to work in English, because it’s such a massive language, and there are so many synonyms, or things with very slight degrees of distinction, so you can communicate very specifically what you want, and also I can use irony, or imagery that is not literal, and people get it. With Toki Pona, I was trying to find the words to express what I wanted to say, and finding it so difficult to be exact that I would then think, “Maybe I shouldn’t bother expressing it!”

NDM: Exactly! And when was the last time you, Helen Zaltzman, thought “Maybe I shouldn’t say this”? So there might be some utility to that.

HZ: I think what Toki Pona has given me is not a new form of communication, but a new way of thinking about communication entirely.

NDM: Mmm. That’s a big statement. Wait - how do you say ‘big statement’? That is ‘pona wawa’. Which is ‘speech that’s strong’.

HZ: I might say it’s ‘pilin suli’ - big feelings.

NDM: Big feelings, that’s true.

HZ: But also ‘pilin lili’ - small feelings.

HZ: If you want to learn Toki Pona, visit tokipona.org for links to the ebook and the very active Facebook group, where you can practice with others.

Nate DiMeo’s gorgeous podcast about moments in history, The Memory Palace, is at thememorypalace.us.

This episode of the Allusionist was produced by me, Helen Zaltzman, with help from Eleanor McDowall and Nate DiMeo. Martin Austwick did all the music that wasn’t Eye of the Tiger. Huge thanks to Sonja Lang.

Which is why, for the last time this fundraiser, I’m dedicating the Randomly Selected Word from the Dictionary to randomly selected Radiotopia donors; I’d like to dedicate it to all of you by name, but to keep this episode under six hours long, I’m dedicating it to four donors: Simon, Louise, Anjali and Mathew’s randomly selected word from the dictionary today is…

kobold, noun (in Germanic mythology): a spirit who haunts houses or lives underground.

Try using it in an email today, Simon, Louise, Anjali and Mathew.

The show will be back in two weeks.